Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious crime after 40 years

For decades, the disappearance of Sheila and Kate Lyon wasn’t just an enduring mystery; it was an unhealed regional trauma. On a March day in 1975, the sisters — daughters of a well-known Washington radio personality — had gone to Wheaton Plaza, a suburban Maryland shopping mall, on an innocent outing, and then vanished. They were never seen again, though the hunt for them was relentless and extensive. Police interviewed countless witnesses and followed hundreds of tips. Every stand of woods or weeds was searched. Storm sewers were explored, as was every vacant house for miles. The residents of a nearby nursing home were interviewed, one by one. Scuba divers groped through mud at the bottoms of ponds. Nothing was found. Nothing came of anything the police did.

I was a green 23-year-old reporter with the Baltimore News-American when the story broke. My job was to show up in the newsroom at 4 a.m. and phone every police barracks in the state, asking whether anything interesting had happened overnight.

When, on the morning of March 26, the desk officer in Wheaton told me about the missing children, I drove directly to the scene. This was a story that was sure to attract attention. Millions of families in the region lived in neighborhoods just like the Lyons’ in Kensington, Md., shooing their kids out the door in the morning and catching up with them at mealtimes, unconcerned about where they went. A story like this struck at suburbia’s idea of itself.

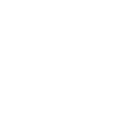

My first story ran two days after the girls vanished, under the headline “100 Searching Woods for 2 Missing Girls.” It had photos of 12-year-old Sheila, in blond pigtails and glasses, and 10-year-old Kate, with her blond hair cut in a cute bob. As days passed with no good news, the tale turned grimmer. In my newspaper the story was still on the front page at the end of the week: “Hope Fades in Search for Girls.” But in time, as nothing happened, the story moved off the front page and then out of the news completely, overtaken by fresh outrages.

As the decades passed I wrote thousands more stories, big ones and small ones. I raised five children of my own. I became a grandfather — of two little blond-haired girls, as a matter of fact. To me, the Lyon story was sad and beyond understanding. Few haunted me as this one did.

While today we can all too readily imagine the disappearance of a child, in 1975 it was shocking — and all the more so because it was two children. Imagining how or why it happened was difficult. The problem of controlling two alarmed children suggested more than one kidnapper, which raised the question, why? What would motivate two people or a group? A sex-trafficking ring? A circle of pedophiles? Just speculating about it conjured scenarios that made you ashamed to be human.

The case haunted the Montgomery County Police Department, too. It was a pebble in the department’s shoe. Generations of detectives had come and gone, and many had taken a crack at it. Periodically, a new team would start over, combing through the many boxes of yellowing evidence, hoping to find something missed. This is what cold case teams do. They embrace the tedium. They are the turners of last stones, laboring in a landscape beyond hope.

But just as the most recent team was preparing to give up, a ray of hope emerged. Detective Chris Homrock stumbled upon a file he had never seen before — the six-page transcript of a statement by an 18-year-old named Lloyd Lee Welch.

On April 1, 1975, Welch, a long-haired drifter with drug and alcohol problems, had contacted Montgomery County police to say that he had witnessed the Lyon sisters’ abduction. Officers had dismissed his elaborate, overly detailed account as a lie, an attempt to insinuate himself into the story, play the hero and collect a reward. But nearly 40 years later, the cold case squad wondered if he really had seen something. At the end of his statement, he had said that the kidnapper walked with a limp, as did the man the detectives, at the time, considered their top suspect. They found Welch in Delaware, at the tail end of a 33-year prison term for molesting a 10-year-old girl, a fact that further piqued their interest.

On Oct. 16, 2013, Detective Dave Davis traveled with Homrock and Montgomery Deputy State’s Attorney Pete Feeney to Dover, Del., to interview Welch, who stunned Dave with the first words out of his mouth. “I know why you’re here,” he said with a sly grin. “You’re here about those two missing kids.”

Related

Six black girls were brutally murdered in the early ’70s. Why was this case never solved?

Lloyd was nothing at all like the reticent man FBI analysts had led the detectives to expect. He appeared to enjoy talking for its own sake, and even though he knew Dave was working on the old Lyon case, he seemed indifferent to the risk. He talked like a man addicted to talk, free-associating, and Dave, who had worried about how to get him going, just sat back and listened.

In that first session, Lloyd denied any involvement with the Lyon girls’ disappearance. “I didn’t kill anybody,” he told Dave. “I didn’t rape anybody. I didn’t do nothin’ to those girls. I mean, I really don’t have much to tell.”

But he went on talking. And after a full day of interrogation, he let slip something that caught the detectives’ attention. The squad had been working on the assumption that Lloyd had witnessed — or possibly assisted in — the girls’ abduction by a pedophile named Ray Mileski. Wrapping up the session, Dave made a final stab at getting Lloyd to reveal something.

“All right, I think they’re, we’re pretty much done,” he said. “But what I wanted to ask — your opinion only — what do you think [Mileski] did to those girls?”

“Personally?” Lloyd asked.

“Yeah, I’m asking you for an opinion.”

“Well, my opinion is that he killed ’em and raped ’em; he killed ’em and he probably burned ’em. I don’t know.”

In the adjacent room, Chris and Pete looked at each other. “Who says ‘burned them’?” asked Pete.

In subsequent sessions with Davis and Homrock, and later also detectives Katie Leggett and Mark Janney, Welch lied elaborately and repeatedly about his connection to the Lyon case. He eventually admitted that he had helped kidnap the girls but insisted that the crime had been planned and carried out by others in his family — first naming a cousin, then an uncle, then his father, who he said had abused him sexually as a child.

In the summer of 2014, the squad began an extensive probe of the entire Welch clan. What the detectives found shocked them. The clan had two branches, one in Hyattsville, Md., and the other five hours southwest, on a secluded hilltop in Thaxton, Va., a place the locals called Taylor’s Mountain. Here the family’s Appalachian roots were extant, even though some members had gradually moved into more modern communities in and around Bedford, the nearest town. While its environs were markedly different, the branch in Maryland clearly belonged to the same tree.

The family’s mountain-hollow ways — suspicion of outsiders, an unruly contempt for authority of any kind, stubborn poverty, a knee-jerk resort to violence — set it perpetually at odds with mainstream suburbia. Most shocking were its sexual practices. Incest was notorious in the families of the hollers of Appalachia, where isolation and privation eroded social taboos. The practice came north with the family to Hyattsville. Here, where suburban families took child-rearing seriously, some adults in Lloyd’s immediate family exploited their offspring and ignored barriers to incest. It was not uncommon for Welch children to experiment sexually with siblings and cousins. If the Lyon sisters had fallen into this cesspool, as Lloyd claimed and the detectives now suspected, then some of the family might have known — and even helped.

At this point, Lloyd was claiming that the chief culprit had been his Uncle Dick, who he said had planned the girls’ kidnapping and then presided over their gang rape, murder and dismemberment. Wiry, flinty and truculent, Dick Welch was nearly 70 but seemed older. In addition to heart trouble, he faced a frightening array of accusations. Various family members had accused him of ugly and violent behavior toward them in the past.

Dick denied it all; he said little, and what he did say was simple and consistent. Indeed, he behaved like someone wrongly accused, bewildered and frustrated by wounding falsehoods. He was summoned to appear before a grand jury in February 2015. When the prosecutor asked him whether he’d had any involvement in the Lyon case, Dick was succinct and firm.

“God as my witness, no.”

“Did you transport one or both of these girls — Sheila and Kate Lyon — from Wheaton Plaza to your residence?”

“No, I didn’t. I’ve never been there.”

“Did you have sexual contact with either Sheila or Kate Lyon?”

“God as my witness, no.”

“Do you have knowledge of any of these things that I’ve talked about?”

“No, but I wish I did.” He had earlier said that he wished he could help the detectives solve the mystery.

“Do you have any explanation why people would say that you did?”

“I don’t know why I’m getting accused, them saying I did this, I done that. I haven’t.”

Pat, Dick’s wife, would eventually be charged with organizing family efforts to stonewall the investigation. Lloyd’s cousin Teddy Welch, the first family member he named as the girls’ kidnapper — though Teddy was only 11 in March 1975 — had run off as a boy to live with a middle-aged man. Two other cousins, Henry Parker and his sister, Connie Parker Akers, still lived near the family homestead on Taylor’s Mountain. Both would prove to be helpful, if reluctant, witnesses to the strange burning of a bloody duffel bag in a bonfire on Taylor’s Mountain, delivered there by Lloyd. Each of these family members and many others told ugly stories of being either victims or witnesses to inter-family sexual assaults.

loyd had emerged from this culture as both victim and predator. After years of wandering and imprisonment, he had strayed far from the family’s grip, but the peculiar values and behavior he had learned (and endured) had not played well in society at large.

By early 2015, the detectives had formed a much fuller picture of Lloyd in 1975. They could look past the sad, pasty, wily, shackled old man who met them in the interview room and see teenage Lloyd: lean, dirty, mean and high. In ordinary times, this might have made him stand out, but in the late 1960s, many teenage boys were growing their hair long, dressing shabbily, infrequently bathing, and experimenting with drugs. For most, this period was a fling. But for Lloyd it was no pose. He really was poor, desperate, dirty and up for anything.

By 1975 the hippie movement had faded, but Lloyd hadn’t changed. He was then part of a class of shaggy vagabonds thumbing their way around the country on back roads, camping in the woods outside suburbia.

Like Lloyd and his girlfriend, Helen, many were heavy drug users. They still proclaimed the fading mantras of the hippie moment — free love, mind-expanding drugs and the all-encompassing “If it feels good, do it” — but few had considered what such a credo might mean to a man like Lloyd Welch.

At 18 he was already an outlaw, stranded on the fringes of a prosperous world beyond his grasp. Shopping malls then were suburbia’s gleaming showcases, lined with high-end stores stocked with goods Lloyd could not afford. And while he was not the sort to reflect on such things, he must have resented the plenitude, all the comforts of money, family and community that he lacked. As Lloyd himself had put it, “I was an angry person when I was young.” And if he felt scorn, or rage, how better to strike back than to stalk the very thing the mall’s privileged customers most prized? The pretty little girls he saw there, to whom he was perversely attracted, represented everything he was denied. Might a man like this have abducted and killed the Lyon sisters?

The detectives came to realize that you had to forget the narrative. The way to read Lloyd was to look past his stories to their details.

Lloyd continued spinning one story after the next to explain what had happened to Sheila and Kate, always placing the blame for the crime on others. But gradually — often inadvertently — he revealed more and more about himself and the crime.

The detectives came to realize that you had to forget the narrative. The way to read Lloyd was to look past his stories to their details. Running through many of his versions were certain particulars that recurred: stalking girls in the mall, an offer to get high, a station wagon, a crying girl in the back seat, a basement hangout accessed from the backyard, rape, drugged girls, a pool room, an ax, the girls “chopped up” and “burned,” an Army green duffel bag, a bonfire. As if in an ever-churning blender, these stubborn nubs kept surfacing. The more they surfaced, the more they began to look true.

On a Monday in May 2015, Dave Davis went looking for the place where Lloyd said Dick had killed and dismembered Kate before stuffing her remains in a duffel bag and ordering Lloyd to take it to Taylor’s Mountain and burn it. It was a secluded spot under a bridge near his uncle’s old home in Hyattsville. Dick went there to fish and drink and smoke. It was his “comfort area.” Lloyd was “90 percent” sure about it.

Dick’s old house had been razed to make room for a new district court building. But Dave knew where it had been, and he went there first.

Right away, Lloyd’s story didn’t add up. The house was the last place you would choose to bring two little girls who were the object of a bicounty manhunt. Even back in the 1970s, before the new courthouse, the address had been a stone’s throw from the city’s police headquarters. There were officers coming and going all the time.

Lloyd had said that there were railroad tracks behind the house and that the bridge over the Anacostia River was a short distance from the front door. But the tracks were in front of the house, not behind, and across Rhode Island Avenue. The river, which was more like a creek, was not even close. The map showed it four blocks east. The layout was nothing like the one Lloyd had described.

Dave next sought out Buchanan Street, which Lloyd had also mentioned and where members of the Welch family had once lived. It was not far away, running southeast from Baltimore Avenue down to the river basin. Dave drove along that route to a dead end that looked down to the water. To the left was a rail bridge that angled across it.

Dave climbed the low fence and walked down to the water. This was clearly the place Lloyd had described, but it was no secluded haven; the angle of the bridge exposed it to views from neighborhoods all around. With all the dealerships and parking lots in the vicinity, it would have been well lit at night. It was like being onstage in a theater-in-the-round. Another Lloyd Welch curveball.

Dave had begun to lose hope of ever sorting out what had happened to the girls. But as he drove back up Buchanan, staring him right in the face across busy Baltimore Avenue was a house he recognized from snapshots in the file. It was the house where Lloyd’s father, Lee, and his wife, Edna, had lived, 4714 Baltimore Ave., a two-story, white-clapboard duplex with pale blue trim and an uneven front porch. This was the address Lloyd had given when he’d made his original false statement. Lloyd had described seeing his uncle pull out of a driveway with the Lyon sisters in his car, heading toward the river — this now made more sense. The location fit Lloyd’s description perfectly, once you saw that it was not his uncle’s house but his father’s.

It struck Dave with the force of revelation. Just as Lloyd always moved himself off-center in his stories, so he had moved this house. The detective pulled over, crossed Baltimore Avenue, and knocked on the front door.

A friendly Hispanic woman who spoke almost no English answered. Dave managed to make himself understood enough to say that he wanted to look at the basement. She showed him that there was no way to enter it through the house. You had to go outside, down the porch, and along the driveway to the backyard, where steps led down to a padlocked door. In every scenario Lloyd had spun, there was a basement hangout, a place where the girls had been kept. He had placed it first in Teddy’s older friend’s home, then in his uncle Dick’s, but in both it was a room that could be entered only by walking around the house to the rear. Once Dave understood how Lloyd’s mind worked, he knew, without question, this had to be the place.

Dave jiggled the latch, and the door opened. He stepped into a dark, low-ceilinged stone dungeon heaped with old furniture. It was so hauntingly familiar it raised the fine hairs on the back of his neck. This was the place. He knew it. It was exactly where one would stash two stolen, frightened, drugged little girls — two rooms completely cut off from the house above. You could do whatever you wished in this space without being seen or heard.

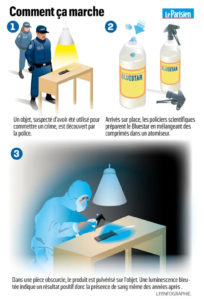

Dave returned the next day with a forensics team. They cleared away some of the old furniture and started squirting Bluestar spray, a blood-detection agent that bonds with even the slightest trace of hemoglobin and glows brightly under a blue light. The floors and walls of the outer room revealed nothing much. Then they cleared debris from the back room and sprayed some more. It lit up from floor to ceiling. It lit up like a murder scene. Someone or something had been slaughtered in this room.

And then Dave knew. All uncertainty vanished. He was even more certain because he had not been led there by Lloyd; he had found it himself. He had extracted it from Lloyd’s stories, bit by bit.

Aglow in blue light, the room announced itself as the place where Sheila and Kate Lyon, lured from Wheaton Plaza, had been drugged, raped and imprisoned, and where at least one of them had been killed and dismembered. Before he had switched the location to a bridge, Lloyd had talked a lot about a basement hangout, his Uncle Dickie’s sanctuary, a place with a locked door, where Dick went to smoke and drink. But it wasn’t Dickie’s basement. It was the basement of Lee’s house, where Lloyd had been living, the space where Lloyd hung out, smoked dope, drank and “partied.” It was his.

Not long after Dave Davis found the likely murder scene, the case against Lloyd was solid enough to charge him with the crime. Whatever illusions he may have had about winning his long-running game with the Lyon Squad were dashed. On Sept. 12, 2017, he pleaded guilty to two counts of felony murder in a Bedford courtroom. Though he still denied that he had raped or killed the sisters, his admission fell well within the confines of a Virginia legal doctrine defining as murder a killing “in the commission of abduction with intent to defile.” He was indicted in the commonwealth because the case against him was stronger there, his cousins having corroborated his final story of driving human remains to Taylor’s Mountain. Lloyd had also several times voiced his fear of execution, so he was considered more likely to accept a guilty plea in Virginia, a death-penalty state — a calculation that proved correct.

The plea spared him from death row, but he would almost certainly never leave prison. His sentence was 48 years. He was 60 years old, and he had, from first to last, talked himself into this outcome.

Although details about their fate — how precisely Lloyd had enticed the girls and what had happened to Sheila — and who exactly was involved remained unsolved, Lloyd’s plea answered my deepest questions: Who would commit such a crime? And why? But I wanted to meet Lloyd Welch. I wanted to size him up for myself, and I also wanted to close the book on the mystery that had been with me my entire professional life. I wrote him a letter requesting an interview and was surprised when he wrote back immediately, saying he would agree to be interviewed if I put $5,000 in his prison account and met certain other terms. I would not meet any of them but offered to discuss them in person.

Sitting directly across from Lloyd felt familiar; I had watched him on video in the interview room for more than 70 hours. He looked thinner than I expected, with a pale pink complexion, and his watery slate-blue eyes were magnified behind his glasses. He was cordial but all business. If I was expecting to look evil in the eye, I was disappointed. What I found was an unimpressive, scheming man, capable of charm but only to the extent that it served his interest, someone natively bright but deeply ignorant and cocky beyond all reason.

If I was expecting to look evil in the eye, I was disappointed. What I found was an unimpressive, scheming man, capable of charm but only to the extent that it served his interest.

He displayed his usual poor sense of situation, believing he had a lot more leverage over me than he did. The terms he repeated were ridiculous, but I heard him out. Then I asked the questions I most wanted him to answer.

“Why did you keep talking to the detectives?”

Lloyd said he had no choice. He said his repeated requests for a lawyer were ignored. Prison authorities told him that he had to continue meeting with the detectives. None of this was borne out by the videos I had watched. His participation throughout had appeared completely voluntary.

Dave Davis had asked me to convey a message. I was to assure Lloyd that his prison account would never be empty if he revealed where the girls’ bodies were. It wasn’t an official offer, but the Montgomery County police had spent millions on the investigation and still didn’t have that answer.

“I have told them all I know,” Lloyd insisted. “Just because a person pleads guilty to something doesn’t mean they are guilty of it. I did not murder or kidnap them girls.”

Who did?

His Uncle Dick was responsible.

“How do you think I would take two little girls out of the mall, kicking and screaming?” he asked. “Who would be able to do something like that? A man with a uniform.” (Dick had worked as a security guard.) He didn’t understand why Dick had not been charged. He said he was afraid of his uncle, as he had been in 1975.

While insisting on his innocence, Lloyd nevertheless seemed a little proud of whatever role he had played in the crime. I told him of my early coverage of the story, and of all the years I had wondered about it. He noted that it had taken the Montgomery County police almost 40 years to link him to the case. “I’ll bet it seemed like the perfect crime, didn’t it?” he boasted.

He complained about being treated as a rapist and child-murderer in the prison. Someone, he said, might still “put a shank” in his back. Then he said he had enjoyed the interview sessions because they got him out of the prison, and he got to eat something better than prison fare. “That’s one of the reasons I kept talking to them,” he said, contradicting what he’d said minutes earlier. He insisted that he had told the detectives the truth throughout, only sparingly. “I was also trying to protect myself.”

By the end of our appointed hour, I saw no strong reason to talk with him further. I had seen him invent and reinvent his version of the story so often that I saw no point in inviting him to do the same with me. But when I wrote back to him a few days later to reject his deal, I added that if he changed his mind about the payment and wanted to talk with me more, I’d come back and listen.

I got another letter from him promptly. “I received your letter and I am very disappointed in this. So let me say this to you so you can understand what I am saying to you. First the documentary you are doing, you may not use any pictures of me or Helen and you may not use my name in anyway at all. … Now, as for your book, I do not give you any permission to use my or any pictures of me or Helen in any way. You do not have my approval or authorization to use anything about the Welch’s name. You may not use any of the interview sessions that you have of me.”

He continued, “Sorry we did not come to some kind of a understanding. … If you want to come see me then you will have to put $300 on my commissary’s books before you can talk to me again. My time is money now.” I noticed that, despite his tone, the price had dropped considerably.

Mark Bowden is an award-winning journalist and author. This article is adapted from his most recent book, “The Last Stone: A Masterpiece of Criminal Interrogation,” published this month by Atlantic Monthly Press.

Credits: Story by Mark Bowden

IAI Annual Educational Conference 2023

August 20-26 Maryland BLUESTAR® Forensic will be present at IAI 2023 Located at the iconic Gaylord National Resort in National Harbor, Maryland, from August 20 to 26,

Forensic PSA Test: BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA® – The Essential Tool for Crime Scene

Forensic PSA Test: “BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA®” An Essential Tool in Forensic Medicine for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Detection In the world of forensic medicine, speed and accuracy

Rose Petal Murder: The Case Involves the Use of BLUESTAR® Forensic Reagent

The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina is drawing national attention and highlights the use of BLUESTAR® Forensic, a blood detection solution.

BLUESTAR® at the 75th AAFS Conference

American Academy of Forensic Sciences 75th Anniversary Conference The American Academy of Forensic Sciences is celebrating its 75th anniversary by hosting the conference entitled “Science

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into evidence, they cleared the floor in order to apply a chemical known as Bluestar, which

KU Leuven Students Investigate Virtual Crime Scenes

Investigating murders as a forensic expert… (India Education : Apr 26, 2022) Taking DNA samples, making blood traces visible with a chemiluminescent spray (‘Bluestar’) or

Forensics, the latest methods

When pollen and insect larvae are used to solve criminal cases and even historical enigmas… This documentary takes a look at the fascinating resources of

How does the scientific police work?

How does the scientific police work?(Le Mag de France Bleu Poitou) (France bleu: January 21, 2022) “To identify the presence of blood that cannot be

Forensic science, clue hunters

Tarbes: Scientific police, the clue hunters La nouvelle république des Pyrénées : November 4, 2021 The technical and scientific police of Tarbes opened us the

Lemerle case: traces of blood revealed by Bluestar

On the first day of Vanessa Lemerle’s trial for the violent confinement of her brother Le quotidien : October 26, 2021 On the first day

A state-of-the-art portable crime lab

Costa Rica’s First Female Forensic Biologist Designed a State-of-the-Art Portable Crime Lab MENAFN : 18.09.2021 In 2010 Tatiana López had to present a University project, she was

“With the blood in the eye” Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials.

“With blood in the eye”. Romano et al. Axis 1 – Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials. Presentation of the paper “With blood in the eye”. Revealing and

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches Neither cadaver dog made strong alerts to seized Volkswagon or Ruben Flores’s property

IAI Annual Educational Conference

Find us at the IAI Annual Educational Conference Nashville August 1-7 Booth 225 Our team will be present at the IAI 2021 conference in Nashville. We will

Troadec case: traces of blood, burning of the bodies, the word of the experts.

The trial of Hubert Caouissin and Lydie Troadec continued with the testimony of experts who worked on the case. France info : 29.06.2021 The trial

Alleged serial killer: new excavations and Bluestar in the orchard

Could the crime scene at Mare-d’Albert be hiding other sordid secrets? In any case, this case, which has been in the news since Friday 28

Police brought Agostina’s alleged femicide to Neuquén

A commission of the local police force transferred Juan Carlos Monsalve from Viedma, accused of being the perpetrator of the femicide. Agustín Martínez LMCipolletti :

Detecting Blood in an Outdoor Environment with the Bluestar Reagent and DNA Analysis

Author(s): McCall, Keenan; Woods, Grace; Richards, Elizabeth Type: Article Published: 2021, Volume 71, Issue 4, Page 309 Abstract: Blood is an important physical material that

Thomas Lesire trial: These clothes are examined with Bluestar reagent

Assizes: trial of Thomas Lesire, accused of the murder of an octogenarian in Châtelet, begins RTBF 03.05.2021 The neighbourhood investigation led the police to a

Daval case: investigation and use of Bluestar

Daval trial: life sentence requested against Jonathann Daval accused of a “terrible” crime, relive the sixth morning of the trial L’est Républicain : 21.11.2020 “When

Case of a missing youth: raids and investigation procedures continue

The procedure was carried out jointly with police personnel from the Forensic Science Department and the 43rd Central Police Station of Jhugua Ñaro and the

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years ABC 13 : 29.06.2020 [United-States/Texas] Donna Brown walked into the Alcoholics Anonymous building

He had tried to erase the trace of the victim’s blood

The baby was beaten and tortured, recorded in bruises, scratches, burns and fractures from the brain down. Photo: Jenny Rocio Angarita Galindo (Radio RCN) Alerta

Policeman’s Memory : a barbaric crime!

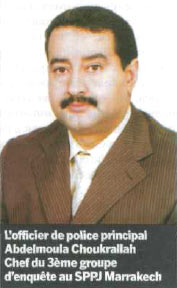

By Fadel ATAALLAH – POLICE magazine N° 57 Octobre 2009 This article reports on a criminal case solved by senior police officer Abdelmoula Choukrallah, head

Narumi case: investigators accuse the main suspect

The Chilean ex-boyfriend of this Japanese student who disappeared in Besançon in 2016 fled to his country. The French justice has just revealed accusing elements

Christine Wood’s DNA found in Brett Overby’s basement, court says

CBC NEWS : 02.05.2019 Christine Wood’s blood was found on a weight bench, closet door and stairs in the basement of a Burrows Avenue home

Bluestar, the miracle product that solves many criminal investigations

Bluestar, which was developed in a CNRS laboratory, has become an essential tool in complex investigations and a formidable weapon in the hands of the

Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious crime after 40 years For decades, the disappearance of Sheila and Kate Lyon wasn’t just

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Murder of a woman by her son

This matricide was solved by the French Gendarmerie Nationale using BLUESTAR® FORENSIC. The woman had been missing for 15 days. BLUESTAR® FORENSIC was sprayed in

Alexia Daval case: other acts and hearings to come

L’est Républicain : 07.07.2018 New forensic expertsAbout forty experts of all kinds have already worked on the case: no less than five forensic doctors; several

JESSIE BARDWELL CASE: WAS TEXAS WOMAN’S DEATH AN ACCIDENT OR MURDER?

A father dreams his daughter has been killed, then she disappears — what does her boyfriend know and could the dad’s nightmare have been an

They capture the partner of a mannequin

The subject claimed that when he arrived at the apartment he found the woman dead, but technical evidence contradicts this version and indicates that he

Scientific advances have made a blood trail speak for itself

Maëlys: how scientific progress made a microscopic trace of blood talk FRANCE 3 : 09.12.2019 They escaped the meticulous cleaning of Nordahl Lelandais. Then, at

Invisible bloodstains revealed by Bluestar

Mallouk case: the long trial of a murder without a confession (FRANCE 3) Hafid Mallouk is to be tried for a fortnight for the murder

A matter of gold and blood

BEHIND THE DISAPPEARANCES OF ORVAULT, THE TROADECS’ FAMILY TRAGEDY (France Info story) A blue and white column slowly progresses through a wooded and soggy landscape.

Killer of elderly woman confesses he had help from hitman

Puno: the killer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman Diario Correo : 27.05.2017 He killed his wife because he

The murderer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman

Puno: the murderer of an old lady confessed having been helped by a hired killer Diario Correo : 27.05.2017 He killed his wife because he

The scene of a crime, suicide or natural death has no mystery for the “cleaners”

It’s a job that is rarely mentioned, as if to ward off bad luck. The very mention of it brings to mind crime scenes seen

Improved detection of Luminol blood in forensics

Review: Improving Luminol Blood Detection in Forensics Florida Forensic Science : 01.03.2017 (Emily C. Lennert) Article to be reviewed: 1. Stoica, B. A. ; Bunescu,

Officers get forensics training

A couple dozen first responders and crime scene investigators gathered around a makeshift crime scene Wednesday afternoon in Jackson. Jackson Sun : 31.12.2016 They watched

Photographing bloodstains

Photographing bloodstains: Bluestar reagent FORENSICS 4 AFRICA 07.07.2016 (Nick Olivier) In the late summer of 2012, police officers in a small Midwestern town were called

Mystery around a disappearance

Yves Bourgade’s murder: BLUESTAR® FORENSIC strengthens suspicions about his wife…

Nisman case: the conclusions of the criminal report

Nisman case: conclusions of the official criminal report point to suicide 11.06.2015 – ARGENTINE – INFOBAE – Infobae has accessed the 97-page document that

Traces of blood were found in his marital home, revealed by the “Bluestar”.

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on telegram Share

The judge in the Yexeira case accepts as evidence another piece with blood on it.

To complete the process of authenticating the evidence, the magistrate noted that the other ICF staff member who received the evidence for analysis would also

20 years of forensic bloodstain analysis in Ontario

While University of Windsor students play with spatter at a forensics conference, provincial police mark the 20th anniversary of bloodstain pattern analysis in Ontario. (Dax

Chief Warrant Officer Benitez left a bloody trail

The clues are accumulating around Chief Warrant Officer Benitez and his involvement in the disappearance of Allison and her mother Marie-Josée on 14 July in

The Flactif case: An investigation solved with Bluestar

At a crime scene, he makes the bloodstains talk “When I entered the Flactif house, I immediately noticed the traces of sponge strokes in the

Photographer Exposes Crime Scenes, With a Dash of Chemistry

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on skype Share

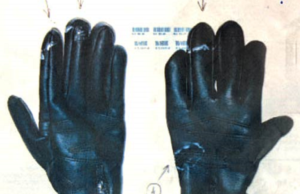

Bloody gloves in Israël

Bloody gloves “catch” Israeli attorney Anat Plinner’s murderer…

Forensics, how does it work?

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on skype Share

Flactif, The cursed cottage is for sale

The parents of Xavier Flactif, massacred with his family in April 2003, have returned to the scene of the tragedy. The chalet of Grand-Bornand, in

The blood of two confederate soldiers revealed at Gettysburg

Gettysburg Civil War case revealed after 142 years !

Suspect arrested on crime scene after his arms turn blue !

A man arrested after his arms turn blue…

The secrets of real experts (LE FIGARO)

Philippe Esperança, morpho-analyst: Blood on the trail By Le Figaro, 21/07/2006. “Espé” is the French specialist in the revelation and analysis of bloodstains. At the

The Flactif case: With Philippe Esperança

BLUESTAR® FORENSIC helped solve the Grand-Bornand quintuple murder case The Flactif family had mysteriously disappeared from their chalet. The programmes “Faites entrer l’accusé” and “Secrets

Shooting of a pedestrian by a driver

A driver shoots and kills a pedestrian…