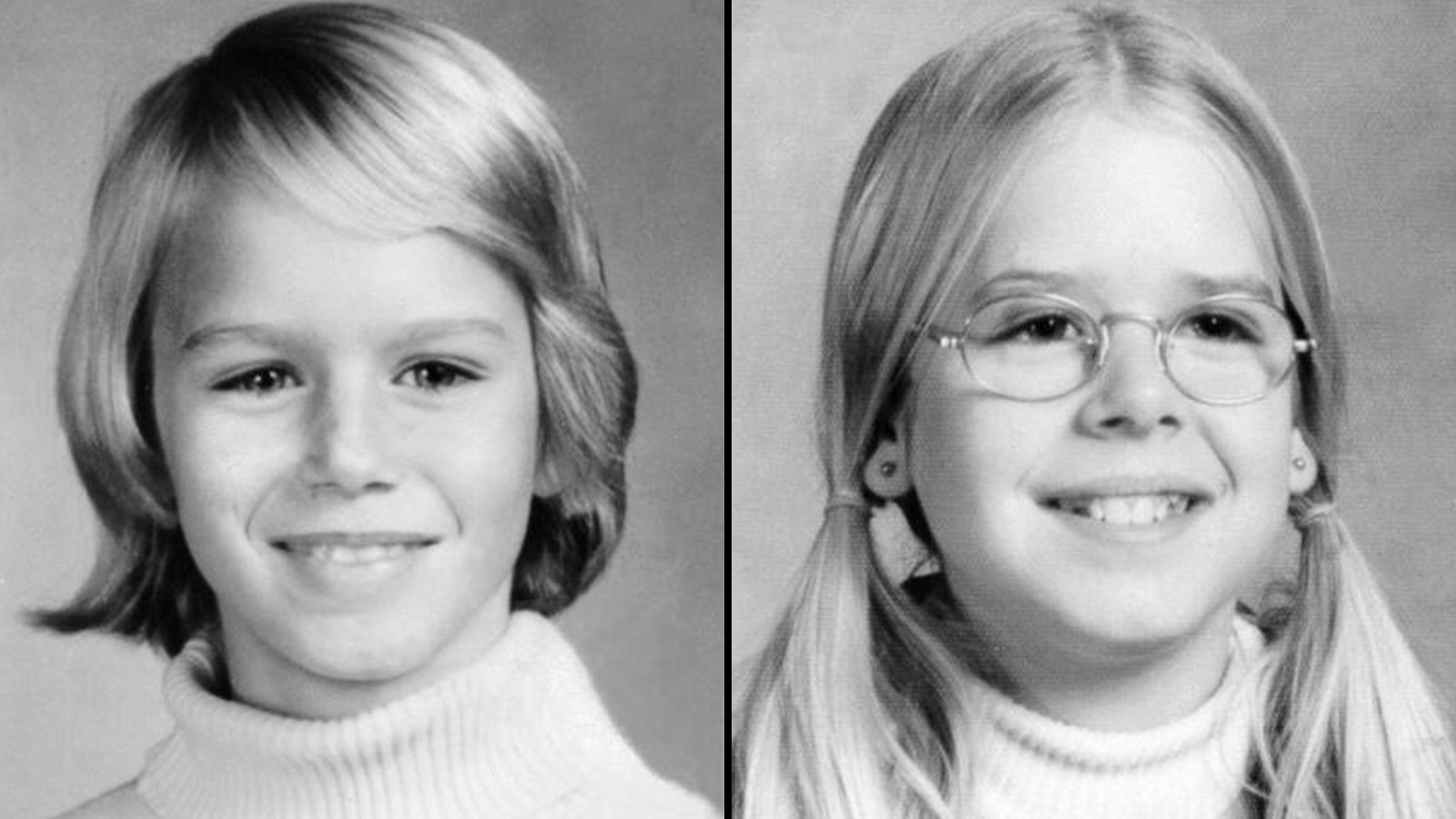

Even without a body, Jason Lowe was charged with murder.

Det. Eric Willadsen: I had no doubt that he had killed her.

But they did have doubts — grave doubts — that they would ever find Jessie.

Det. Eric Willadsen: Texas is a huge state. We’ve got lots of rivers, lots of lakes, lots of ponds, fields. There are — 100 million different places you could hide a body in Texas.

Back home in Pascagoula, the town rallied around the family.

Kitty Bardwell | Jessie’s grandmother: They had a candlelight vigil at the beach … praying that she’d be found, maybe safe somewhere.

On May 19, almost three weeks after Jessie was last seen alive, they finally got an answer. The police had reason to believe Jessie was on a remote ranch in North Texas. Gary Bardwell says they wouldn’t tell the family how they knew; only that it was a reliable source. Chief Jimmy Spivey called the Bardwell family into the station.

Gary Bardwell: The chief said, “It’s gonna be a bad day for y’all today because we do not expect to find your daughter alive.”

A team of detectives, FBI investigators, and prosecutors made their way to that remote ranch in Farmersville, Texas. They arrived late afternoon and started walking through the fields.

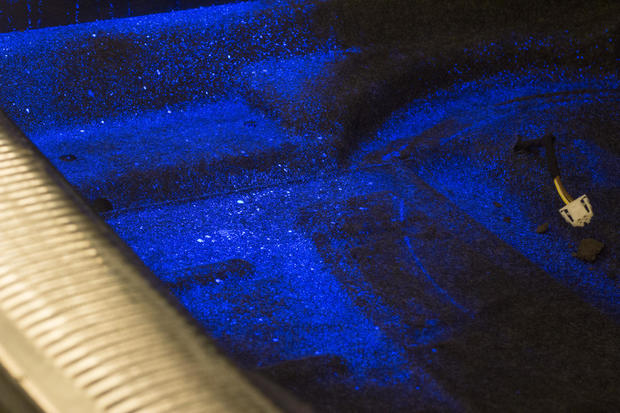

Det. Eric Willadsen: We saw where he had gotten stuck in the mud.

Maureen Maher: You could still see the car parts on the ground?

Det. Chiron Hale: You could.

Det. Eric Willadsen: We found a piece of metal…looked like it was shielding something — kind of a makeshift burial area, and at that point you could start to smell, you know, decaying flesh, so…

Det. Eric Willadsen: …we walked closer. She was covered with a sheet, so you could tell — but you could see the outline of the body under the sheet.

Jessie Bardwell had been crudely wrapped in a blue fitted sheet and covered with a pile of debris, including a red blanket and two red and gold towels.

Maureen Maher: What was the condition of this body?

Det. Eric Willadsen: It’s one of the worst we’ve seen.

It would take seven days to officially identify her body. The medical examiner ruled Jesse’s death a homicide. But her body was so badly decomposed officials could not say how she was murdered.

Against his better judgment, Jessie’s father read the autopsy report.

Gary Bardwell [overcome with emotion]: I felt it was my responsibility as Jessie’s daddy to read the report. …she was brutally murdered. And she was thrown away like a piece of trash … wrapped up in a sheet barely looking like a person.

Gary Bardwell [overcome with emotion]: They sent the hearse to Texas to pick her up and my firemen buddies loaded her into the back of the hearse … This is my life now.

Over 900 people showed up at First United Methodist Church to mourn the death and celebrate the life of 27-year-old Jessie Bardwell.

Kitty Bardwell: If this town could be washed with all the tears that were shed over Jessie, it’d be real clean. We wouldn’t even need for it to rain for the tears that were shed for Jessie.

While the Bardwells spent the next year grieving, a very different looking Jason Lowe was in a McKinney, Texas, jail cell preparing his defense.

Andy Farkas | Defense attorney: One of the key issues in this case is whether or not to have our client testify.

Jason’s court appointed attorney, Andy Farkas, says he is sure that Jason did not murder Jessie. He’s not so sure Jason can convince a jury. But he has a plan.