To complete the process of authenticating the evidence, the magistrate noted that the other ICF staff member who received the evidence for analysis would also testify.

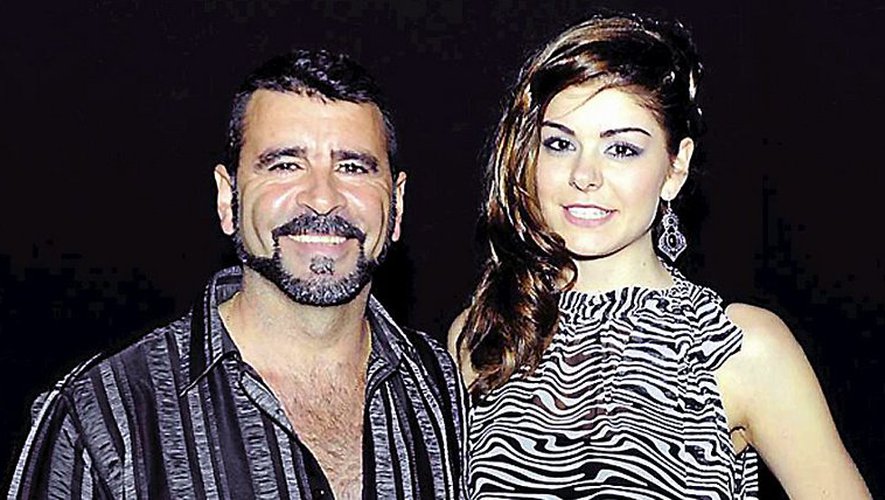

Judge Francisco Borelli Irizarry of the Carolina court admitted on Friday the black tarpaulin of Roberto Quiñones Rivera’s van, where the blood stains of his girlfriend Yexeira Torres Pacheco would have appeared, as evidence conditioned by the prosecution.

Borelli Irizarry explained that forensic investigator David Betancourt Quiñones of the Forensic Institute (ICF) had not identified his marks on the object and could not explain why the piece was not complete. He also did not identify any other marks contained on the tarpaulin, which he removed from the vehicle on 16 November 2011.

To complete the process of authenticating the coin, the magistrate said that the other ICF official who had received the coin for analysis still had to testify.

In the continuation of the case against Quiñones Rivera for the death and disappearance of the body of Yexeira, choreographer and dancer of the rapper Miguelito, Betancourt Quiñones explained that he examined the defendant’s white Ford Econoline bus on two occasions to identify the blood hidden in the vehicle.

She also examined a construction level occupied by the police in the bus to try to identify fingerprints.

The first assessment was carried out on 16 November at the ICF in Rio Piedras, at the request of investigating officer Lorimel Aquino Fariña.

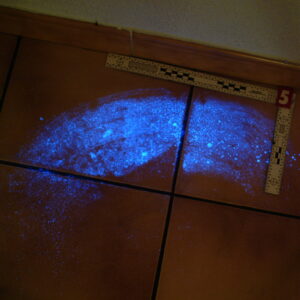

He explained, in response to questions from prosecutor Alma Mendez Rios, that he had used the chemical “bluestar” to detect the possible presence of blood on the van.

“Bluestar is an improved formulation of luminol. You can use it over and over again and it doesn’t damage the sample,” said the witness, who testified in the afternoon.

He said that spraying the chemical on the bus “produced a bright luminescence at the back, near the front seats of the bus”. “I took the whole tarpaulin because it was very luminescent and I decided to have it analysed by the laboratory,” he said. He added that he did not want the sample to be diluted or fragmented. He then detected small spots of apparent blood on the inside of the passenger door.

These marks, he said, were on the inside frame of the door, at the back where the door locks, at the base of the rear view mirror and in the middle of the door panel. In his theory of the case on the first day of the trial, prosecutor Mendez Rios said the blood that appeared in the vehicle came from the body of a woman who was the daughter of Victor Torres Santiago and Iris Pacheco Calderon, Yexeira’s parents. He also said that analysis of the blood traces found in the bus will show that Yexeira bled to death on the passenger seat and was then dragged into the back of the van.

False number plate

In the morning, Officer Jose Dennis Rivera of the police stolen vehicle division, who removed the fake tag from the defendant’s van on November 10, 2011, testified.

In the morning, Officer Jose Dennis Rivera of the police stolen vehicle division, who removed the fake tag from the defendant’s van on November 10, 2011, testified. The witness explained that there were inconsistencies between the date on the vehicle’s driving licence and the tag that authorized the vehicle to travel on the country’s roads.

The vehicle registration, which was not stamped, indicated that the licence had expired on 31 October 2011, but the label had an effective date of December 2011. “(The licence) was not stamped like when you buy the sticker,” he said. He also noted that the colour of the label was distorted and had an irregular cut in the circle marking the month of December.

After taking the label, he went to an office of the Ministry of Transport and Public Works, where he was told that the label was fake. Jorge Gordon Menendez attempted to challenge the officer’s work by pointing out that he never asked to see the new vehicle registration and insisting that because of the ease with which the witness removed the tag, it could have been affixed to the vehicle’s window shortly before he took it.

Quiñones Rivera is currently serving a 42-month prison sentence for the false tag and the illegal appropriation of a police bullet-proof waistcoat.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Year

Country

Archives

- July 2023

- March 2023

- September 2022

- April 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- May 2017

- March 2017

- August 2016

- July 2016

- January 2016

- June 2015

- July 2014

- March 2014

- September 2013

- June 2013

- December 2010

- June 2010

- January 2010

- March 2009

- March 2008

- September 2007

- July 2006

- August 2005

Forensic PSA Test: BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA® – The Essential Tool for Crime Scene

Forensic PSA Test: “BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA®” An Essential Tool in Forensic

Rose Petal Murder: The Case Involves the Use of BLUESTAR® Forensic Reagent

The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina is drawing national attention and …

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into

KU Leuven Students Investigate Virtual Crime Scenes

Investigating murders as a forensic expert… (India Education : Apr

Forensics, the latest methods

When pollen and insect larvae are used to solve criminal

How does the scientific police work?

How does the scientific police work?(Le Mag de France Bleu

Forensic science, clue hunters

Tarbes: Scientific police, the clue hunters La nouvelle république des

Lemerle case: traces of blood revealed by Bluestar

On the first day of Vanessa Lemerle’s trial for the

A state-of-the-art portable crime lab

Costa Rica’s First Female Forensic Biologist Designed a State-of-the-Art Portable

“With the blood in the eye” Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials.

“With blood in the eye”. Romano et al. Axis 1

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on

Troadec case: traces of blood, burning of the bodies, the word of the experts.

The trial of Hubert Caouissin and Lydie Troadec continued with

Alleged serial killer: new excavations and Bluestar in the orchard

Could the crime scene at Mare-d’Albert be hiding other sordid

Police brought Agostina’s alleged femicide to Neuquén

A commission of the local police force transferred Juan Carlos

Detecting Blood in an Outdoor Environment with the Bluestar Reagent and DNA Analysis

Author(s): McCall, Keenan; Woods, Grace; Richards, Elizabeth Type: Article Published:

Thomas Lesire trial: These clothes are examined with Bluestar reagent

Assizes: trial of Thomas Lesire, accused of the murder of

Daval case: investigation and use of Bluestar

Daval trial: life sentence requested against Jonathann Daval accused of

Case of a missing youth: raids and investigation procedures continue

The procedure was carried out jointly with police personnel from

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after

He had tried to erase the trace of the victim’s blood

The baby was beaten and tortured, recorded in bruises, scratches,

Policeman’s Memory : a barbaric crime!

By Fadel ATAALLAH – POLICE magazine N° 57 Octobre 2009

Narumi case: investigators accuse the main suspect

The Chilean ex-boyfriend of this Japanese student who disappeared in

Christine Wood’s DNA found in Brett Overby’s basement, court says

CBC NEWS : 02.05.2019 Christine Wood’s blood was found on

Bluestar, the miracle product that solves many criminal investigations

Bluestar, which was developed in a CNRS laboratory, has become

Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Murder of a woman by her son

This matricide was solved by the French Gendarmerie Nationale using

Alexia Daval case: other acts and hearings to come

L’est Républicain : 07.07.2018 New forensic expertsAbout forty experts of

JESSIE BARDWELL CASE: WAS TEXAS WOMAN’S DEATH AN ACCIDENT OR MURDER?

A father dreams his daughter has been killed, then she

They capture the partner of a mannequin

The subject claimed that when he arrived at the apartment

Scientific advances have made a blood trail speak for itself

Maëlys: how scientific progress made a microscopic trace of blood

Invisible bloodstains revealed by Bluestar

Mallouk case: the long trial of a murder without a

A matter of gold and blood

BEHIND THE DISAPPEARANCES OF ORVAULT, THE TROADECS’ FAMILY TRAGEDY (France

Killer of elderly woman confesses he had help from hitman

Puno: the killer of an old woman confessed to having

The murderer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman

Puno: the murderer of an old lady confessed having been

The scene of a crime, suicide or natural death has no mystery for the “cleaners”

It’s a job that is rarely mentioned, as if to

Improved detection of Luminol blood in forensics

Review: Improving Luminol Blood Detection in Forensics Florida Forensic Science

Officers get forensics training

A couple dozen first responders and crime scene investigators gathered

Photographing bloodstains

Photographing bloodstains: Bluestar reagent FORENSICS 4 AFRICA 07.07.2016 (Nick Olivier)

Mystery around a disappearance

Yves Bourgade’s murder: BLUESTAR® FORENSIC strengthens suspicions about his wife…

Nisman case: the conclusions of the criminal report

Nisman case: conclusions of the official criminal report point to

Traces of blood were found in his marital home, revealed by the “Bluestar”.

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

The judge in the Yexeira case accepts as evidence another piece with blood on it.

To complete the process of authenticating the evidence, the magistrate

20 years of forensic bloodstain analysis in Ontario

While University of Windsor students play with spatter at a

Chief Warrant Officer Benitez left a bloody trail

The clues are accumulating around Chief Warrant Officer Benitez and

El suboficial mayor Benítez dejó un rastro sangriento

Las pistas se acumulan en torno al suboficial mayor Benítez

L’adjudant-chef Benitez a laissé un sillage sanglant

Les indices s’accumulent autour de l’adjudant-chef Benitez et de son

The Flactif case: An investigation solved with Bluestar

At a crime scene, he makes the bloodstains talk “When

Photographer Exposes Crime Scenes, With a Dash of Chemistry

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

Bloody gloves in Israël

Bloody gloves “catch” Israeli attorney Anat Plinner’s murderer…

Forensics, how does it work?

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

Flactif, The cursed cottage is for sale

The parents of Xavier Flactif, massacred with his family in

The blood of two confederate soldiers revealed at Gettysburg

Gettysburg Civil War case revealed after 142 years !

Suspect arrested on crime scene after his arms turn blue !

A man arrested after his arms turn blue…

The secrets of real experts (LE FIGARO)

Philippe Esperança, morpho-analyst: Blood on the trail By Le Figaro,

The Flactif case: With Philippe Esperança

BLUESTAR® FORENSIC helped solve the Grand-Bornand quintuple murder case The

Shooting of a pedestrian by a driver

A driver shoots and kills a pedestrian…