The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina is drawing national attention and …

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

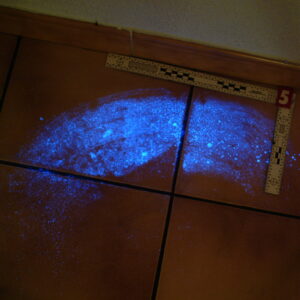

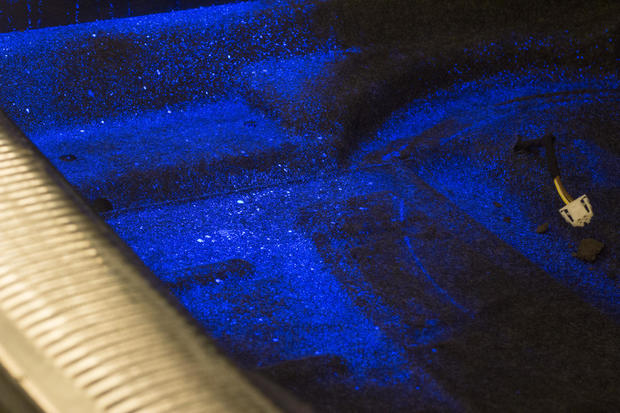

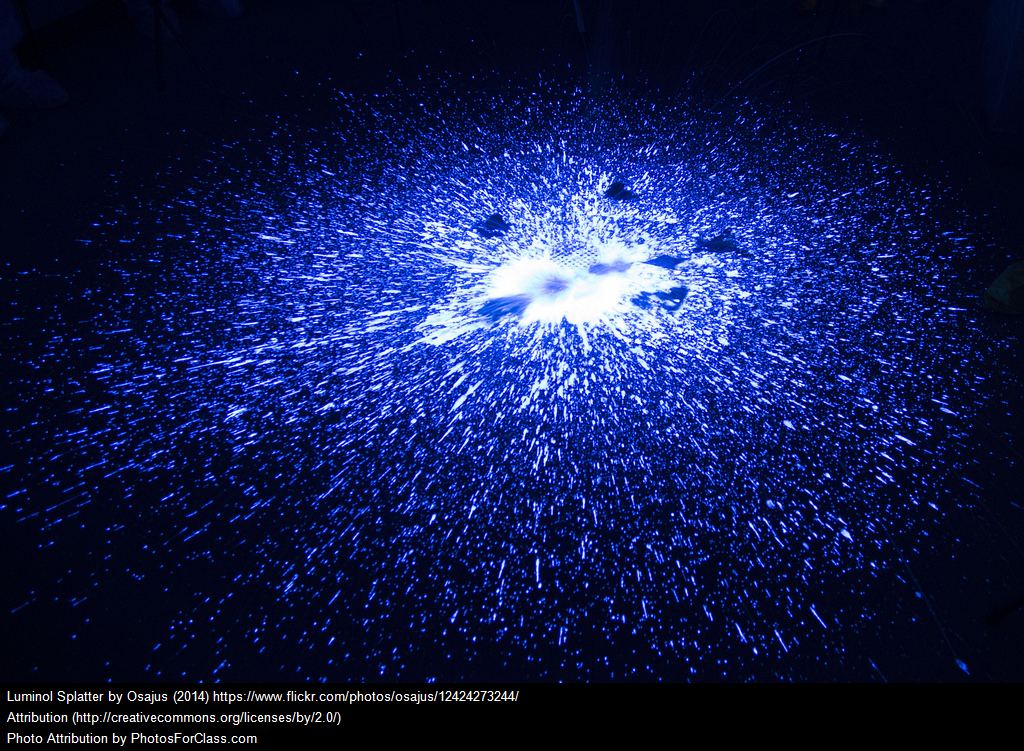

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into evidence, they cleared the floor in order to apply a chemical known as Bluestar, which lights up blue when it comes into contact with human blood, Liddell said.

What did investigators find under Ruben Flores’ deck? Expert testifies in Kristin Smart trial

The Tribune: September 07, 2022

Traces of human blood were possibly found inside a trailer at Ruben Flores’ home, a San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Office forensic specialist testified Wednesday during the Kristin Smart murder trial.

Shelby Liddell, who spoke on the stand in Monterey County Superior Court, has been a forensic specialist for the Sheriff’s Office for about four years. She helped excavate parts of Flores’ Arroyo Grande property, in particular an area underneath his deck — where investigators believe Smart’s body was once buried after his son, Paul Flores, allegedly killed her in 1996. On Wednesday, San Luis Obispo County Deputy District Attorney Chris Peuvrelle walked Liddell through two 2021 excavations she did at Ruben Flores’ home. During the excavations, Liddell said, she helped dig at various areas and helped identify a stain discovered in the dirt beneath Flores’ deck.

Samples of the stain — which archaeologist Christine Arrington previously testified was likely from human remains — was collected as evidence and subsequently subjected to test for human blood and DNA, Liddell testified. She said she focused on carefully collecting soil from the darkest parts of the stain for testing. She said she also collected control samples of soil from various parts of the property, including under the deck, to ensure the samples from the stain could be tested accurately.

EXPERT: CHEMICAL INDICATES PRESENCE OF HUMAN BLOOD IN TRAILER

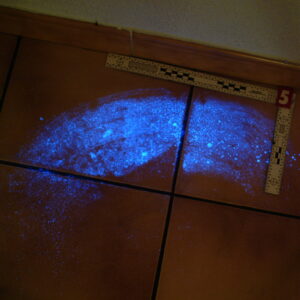

A cargo trailer was taken from Ruben Flores’ home to the crime lab annex for further testing, Liddell said on the stand Wednesday. The trailer belonged to Mike McConville, boyfriend of Ruben Flores’ ex-wife, Susan Flores. After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into evidence, they cleared the floor in order to apply a chemical known as Bluestar, which lights up blue when it comes into contact with human blood, Liddell said. The chemical may also react to some paints or varnishes, certain animal blood and cleaning chemicals.

“However the reaction is different” in those cases, she testified.

For example, Liddell said, when the chemical comes into contact with a cleaning chemical such as bleach, it more closely resembles a bright flash and is more white than blue. When it comes into contact with human blood, however, it is more of a slow blue glow — “like that photo,” she said, pointing to a photo of the blue glow emitted on the cargo trailer. The reaction site was on the floor of the inside of the side door of the trailer, the photo showed. While the Bluestar reaction is not direct evidence itself, “it is used as a presumptive to narrow down the search for collection for further testing,” Liddell said.

WITNESS CHANGED PREVIOUS TESTIMONY FOR ‘CLARIFICATION’

On cross-examination, Paul Flores’ defense attorney, Robert Sanger, noted that Liddell’s testimony had changed from what she said during the preliminary hearing — specifically about whether the stain underneath the deck was disturbed.

On cross-examination, Paul Flores’ defense attorney, Robert Sanger, noted that Liddell’s testimony had changed from what she said during the preliminary hearing — specifically about whether the stain underneath the deck was disturbed. In the preliminary hearing, Liddell stated that it did not seem the stain had been disturbed prior to excavation, but in her testimony Wednesday she said it had. When Peuvrelle asked her to explain her answer, Liddell testified she “was taking (Sanger) too literally” and thought he meant the stain itself, not the area around the stain. Liddell said she was provided transcripts of her testimony from the preliminary hearing and reviewed them before giving her testimony Wednesday, but had not conferred with the prosecution about changing her testimony.

She also did not review any reports indicating the change, she said. Liddell testified Wednesday that she decided to clarify her answer because she realized her previous testimony was not clear. Throughout her testimony, Liddell declined to answer questions about how the stain and soil interacted with one another because her expertise is in evidence and DNA collection. “I am not an expert in staining and soil. That’s why we brought in the archaeologists,” she said. This was a point that Ruben Flores’ defense attorney, Harold Mesick, focused on during Wednesday’s cross-examination.

Liddell spoke about taking samples from stained soil and discolored soil. After confirming Liddell did not consider herself an expert in staining and soil, Mesick asked her what the difference was between the two.

She did not immediately answer, and Mesick put a photo of the stain up on the projector and asked her to explain it. She said the larger section is a stain, and the different colors in the middle of the stain were discoloration. Also, while Liddell talked with the archaeologists at the scene, she decided what samples to take on her own, she testified. Liddell testified that no bones, teeth or hair were found at any of the excavations sites she examined — including sites at the Flores home, three in Huasna and one in rural Arroyo Grande, Liddell testified. “Any semi-permeable wraps?” Sanger asked, referring to the prosecution’s theory that Smart was wrapped in a semi-permeable wrap while buried underneath Ruben Flores’ deck. To her knowledge, no evidence of a semi-permeable wrap was found, Liddell testified. Court will resume Thursday with a “full day of testimony,” Monterey County Superior Court Judge Jennifer O’Keefe told the juries, urging them to be on time.

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches Neither cadaver dog made strong alerts to seized Volkswagon or Ruben Flores’s property

Paso Robles Press : Sep 3, 2021

SAN LUIS OBISPO — Two cadaver dog handlers and a forensic specialist testified in court on Thursday, Sept., 2 in the preliminary hearing for Paul (44) and Ruben (80) Flores.

The father and son are charged in connection with the 1996 disappearance and murder of 19-year-old Cal Poly student Kristin Smart. Paul has been charged with her murder, and Ruben is being charged with accessory after the fact. Both men were arrested in April. Ruben is out on bail, but Paul remains in the San Luis Obispo County jail with no bail.

Getting through this together, Paso Robles

Kristin’s remains have never been found, but she was declared legally dead in 2002.

Kristine Black, Karen Atkinson, and their cadaver dogs were called to search under the back porch of Ruben Flores’ home in the 700 block of White Court after warrants were executed on the residence in March and April of this year.

Both women are Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office Canine Specialized Search Team handlers. Both dogs are certified in human remains detection through the California Rescue Dog Association, according to testimony.

As the assistant director for the search and rescue team, Black talked about her search of Ruben’s home on White Court in Arroyo Grande on March 15.

She said she brought her Belgian Malinois, Annie, with her and first searched a maroon 1985 Volkswagon that was later seized from Ruben’s home as part of the investigation.

Black says Annie, who is only trained in detecting human remains, went inside the vehicle but did not have a final response. They headed into Ruben’s backyard next.

Black said she intentionally stood out of sight from the house at the end of White Court in order to not influence her search.

She testified that Annie started to show changes in behavior in an area under the left side of the deck behind some lattice. While the behavior change was consistent with odor, Black says Annie did not go to a final response, instead of putting her nose down and changing her breathing and snorting hard while circling the area.

Atkinson testified that she searched the property with her dog, Amiga, on the same day and had the same results.

She noted a slight change in behavior in Amiga as she worked a long, narrow area that sloped up near the foundation. According to Atkinson, Amiga began to sniff and make “head pops,” which indicated she detected an odor. Atkinson described the change in behavior as being characteristic for when Amiga detects her target odor – human remains – but Atkinson says the dog’s alert is sitting, which she did not do.

Attorney Sarah Sanger, who represents Paul with her father Robert Sanger, questioned whether a change in behavior is not an alert. Atkinson explained Amiga will not alert until she reaches the strongest point of the odor. Harold Mesick, Ruben’s attorney, questioned whether Black searched any trailers on the property, to which she replied no. During the afternoon session, the court heard testimony from a forensic specialist with the San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Office.

Shelby Liddell talked about two different searches at Ruben’s home on Mar. 15 and 16, 2021. She was assigned to process the scene at 710 White Court, including taking photos and collecting soil samples. Liddell testified that at three feet deep, while detectives were digging up under the deck in the backyard, they started noticing staining in the soil. According to Liddell, dark staining was noticed down to four feet. She told the court she collected samples along with control samples around the property.

She said she returned on Apr. 13 and 14 to collect more samples from under the deck again.

Liddell also testified to spraying the inside of the trailer seized from the Flores’ residence with Bluestar, a forensic chemical used to detect blood and other bodily fluids.

According to the sheriff’s Detective, Clint Cole, the trailer belonged to the boyfriend of Susan Flores, Paul Flores’ mother, and was seized on the belief that it was used to transport the remains of Smart from Ruben Flores’ residence in February 2020.

Liddell said that 30 minutes after spraying Bluestar, a blue luminescent stain approximately a foot-and-a-half wide appeared on the inside of one of the trailer’s doors, which was documented with a camera.

Bluestar, which reacts to the hemoglobin in human blood and is a proprietary formula, can also show false positives for cleaning materials and some types of vegetables. However, according to Liddell, the reaction is typically a “white flash” that goes away after a while.

The preliminary hearing resumes at 9:30 a.m. on Friday, Sept. 3, at the San Luis Obispo County Superior Courthouse.

Detecting Blood in an Outdoor Environment with the Bluestar Reagent and DNA Analysis

Author(s): McCall, Keenan; Woods, Grace; Richards, Elizabeth

Type: Article

Published: 2021, Volume 71, Issue 4, Page 309

Abstract: Blood is an important physical material that may be encountered in violent crimes such as murder, assault, and rape.

The examination of bloodstains is of immense value in the reconstruction of crime scenes and the potential identification of subjects and victims and their linkage to a scene.

When crime scenes occur outdoors, the identification of blood evidence can become difficult with the naked eye.

The objective of this research was to conduct examinations of the Bluestar reagent to determine whether it could successfully detect blood in outdoor sites after prolonged exposure to the elements and whether the identified blood could produce a DNA profile.

Bluestar advertises the ability to reveal bloodstains that have been washed out, wiped off, or which are invisible to the naked eye.

For this research, approximately 0.5 oz of human blood was deposited onto the soil surface of 30 plots to be tested over 10 time intervals up to 45 days. At each interval, a soil sample and a cotton swab of the plot‘s surface were collected for later DNA testing. Results showed a positive Bluestar reaction throughout all intervals of the experiment. DNA profiles were developed from cotton swabs while the blood was visible to the naked eye.

Some of the soil samples returned weak profiles that could not be correlated to the donor. The results of this study demonstrate that even if there is a delay in locating an outdoor crime scene, the application of Bluestar is a reliable tool in the effort of locating blood evidence.

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Galveston AA group leader's killer is still out there after 2 years

ABC 13 : 29.06.2020 [United-States/Texas]

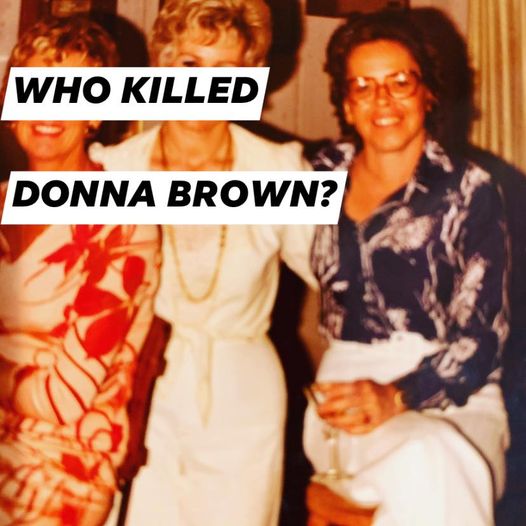

Donna Brown walked into the Alcoholics Anonymous building in Galveston to prepare for the meeting she planned to host that afternoon, and was murdered.

It was an AA volunteer who found Donna laying in the doorway. The 79 year-old was still alive. The volunteer called 911.

“She’s laying here motionless and there’s blood on the floor,” the caller told dispatch. The caller initially thought Donna had slipped and fallen. When paramedics arrived, Donna still had a faint pulse. EMTs loaded her into an ambulance and when they cut away Donna’s shirt, they realized she hadn’t fallen. She had been stabbed. In Ohio, Elizabeth Rogers got the call about her great-aunt.

“How anybody could stab somebody that many times and make them look like that? How somebody could do that – to put them through so much pain,” says Rogers. “She just looked grotesque. Such a beautiful woman and she looked so incredibly awful.”

Rogers bought a plane ticket to Texas and less than 24 hours later, she was standing in the ICU, saying goodbye to the woman she had been in awe of her whole life.

Donna had been the “cool aunt.” She was a Pan Am stewardess in the sixties, jet-setting all over the world. She never married and lived in West Palm Beach for most of her life. Rogers says Donna made money in stocks and investing well – progressive for a single woman at that time. But, about 20 years ago, Donna made a bad investment that changed her life, Rogers says.

“She lost all of her money. She, instead of filing bankruptcy, she just paid everything off and started over. She came out here and she pulled herself up by her straps,” Rogers says.

When Donna lost that money, she moved to Galveston and lived modestly.

“It’s such an amazing story of how you can make it work. She didn’t bring in a lot of money each month. Very little, actually,” Rogers says. “She didn’t care about the material things. Her focus was on helping people.”

That’s what brought Donna to Alcoholics Anonymous. She organized a “women only” group that met Sunday afternoons at 4 p.m. and women showed up week after week. They grew to depend on Donna.

Grainy surveillance video from an apartment complex across the street captured the last moments of Donna’s life. It’s never been seen by the public, until now.

The video shows 3:43 p.m. when Donna pulls up in her white hatchback. Two minutes later, you see her cross the street. She walks through the mint-green colored side door of the AA building on the corner of 33rd Street and Avenue P . After Donna walks in, you see the door open a second time.

“You see what appears to be a struggle in that doorway, ” says Detective Michelle Sollenberger with the Galveston Police Department. “Then, the door slams closed. And we know that Donna was found by her associate at the AA Hall right inside that doorway.”

Why would anyone want to kill Donna?

She was known as a feisty woman. Police say some fellow group members described her as “cantankerous.”

“Donna was known for running men out of the meeting hall for the women’s meeting on Sunday afternoon,” Sollenberger says. “Everybody said: if there was a man in that meeting hall, Donna would have run him off. She would have probably been hollering at him and telling him to get out of there. Unfortunately, this person has a very volatile temper and snapped.”

Donna isn’t the only one seen on that surveillance video. So is the killer, detectives think.

A person is seen entering the other side of the AA building, two hours before Donna showed up. He appears to be wearing black or dark jeans and has on a backpack.

This is what sets Donna’s unsolved murder apart from other cold cases. Detective Sollenberger thinks she has the murderer: she just needs more evidence to connect the dots.

“It’s so frustrating. It’s really so frustrating,” she says.

One man may be the key to solving this. We’ll call him Scott. That’s not his real name. He didn’t want to be identified, because the killer is still out there. Scott says he’s sure he was face-to-face with Donna’s killer hours before she was murdered.

In the surveillance video, you see Scott ride up to the AA hall on his bike, 26 minutes after the first man walked in. Scott parks and goes into the brick building.

“When I went inside, there was a gentleman that was passed out-not passed out, but he was laying on one of the benches inside,” Scott says. “My bag was next to him as was all my stuff. The bag was opened and all my stuff-everything had, you know-somebody had gone through my stuff.”

Scott says he and the man got into it.

“This gentleman sat up and said, ‘I went through all your stuff to make sure there wasn’t a bomb in it.’ And he just kind of did a little chuckle and it really got me hot, you know?” Scott says. “This guy is an intimidating guy, kind of a scary person. He’s a big guy. He’s young and probably twice my size and he’s fit. He (was) just really aggressive, very animated, very aggravated.”

Scott grabbed his bag and got out of there. Surveillance video shows him inside for a total of two minutes. You see him ride off on his bike 90 minutes before Donna arrived.

A couple days after her murder, Scott worked up the courage to tell police what had happened.

“He was able to identify the person as somebody he knew from the meetings. But, the nature of the AA program is to be anonymous, and so, a lot of the individuals don’t know each other,” Sollenberger says.

That made Sollenberger’s job harder but not impossible. She tracked down the person Scott says he thinks he spoke with in the AA building before Donna was attacked. Sollenberger had to figure out: was he the killer? Was he the man in the video wearing black pants and the backpack? We’re not naming him because he’s not a suspect. He’s a person of interest.

Two days after Donna’s murder, the man was arrested on an unrelated warrant. Police collected his clothes and shoes. CSI techs sprayed a special liquid called Bluestar on the man’s tennis shoes. The liquid glows blue under a blacklight if someone’s DNA is present. His shoes lit up. But, testing at the crime lab can’t confirm whose DNA is present.

“It was really frustrating because we thought that bloody shoe was going to be the missing piece of our puzzle.”

Sollenberger says the man with the blue shoe told her he had an alibi. He was at church about a mile from the AA hall when Donna was killed. But Sollenberger says the man told her he wasn’t there.

Weeks passed-and then, another break. A neighbor living near the AA building called police with new surveillance video from his Ring doorbell. It showed a man with dark pants and a backpack coming from the direction of the hall, five minutes after Donna was murdered.

Sollenberger released that video exclusively to ABC13, hoping someone sees it and can identify the man by name.

“I think that would be the linchpin in this case,” she says. “We’ve exhausted the forensics and we have essentially run out of leads because of the anonymity involved in some of the witnesses and people involved in the AA hall.”

A few months away from the second anniversary of Donna’s death, Elizabeth Rogers flew from Ohio to Texas again, to visit the AA building for the first time.

“It’s a little surreal. It’s good though. It’s really good,” Rogers told us. “It brings it all back. It makes me want to resolve this for her.”

Rogers met Scott, who says he thinks about that day every day.

“That could have been me. That very well could have been me,” he says.

Before he met Donna, Scott had been struggling to stay clean. Now, he has a job, he has a home, he has a life-he says it’s all thanks to Donna:

“God brought that lady to my life. That was not by mistake. That happened for a reason. She’s a hero to me. I don’t even know her. But she kept me praying and that’s what’s kept me alive.”

Since the pandemic hit, Sollenberger says she’s had more time to work on cold cases like Donna’s. But, interviewing people in person can be tough with a mask.

Coronavirus stopped AA meetings in Galveston for a while. Donna would have struggled with that.

“She was just the person who happened to be there. It would have been anyone who walked through that door,” Sollenberger says.

Someone knows who killed Donna Brown-knows why it happened and where the murder weapon is hidden.

“To believe the suspect didn’t tell somebody is a little farfetched. I think he had to have relayed this information to somebody at this point,” Sollenberger says.

Donna’s family is asking for your help. Because that’s what Donna stood for: she helped people who, in many cases, didn’t have anyone. Donna wouldn’t let them be forgotten.

“I’m going to keep at it,” Rogers says. “I’m going to keep at it no matter what it takes. No matter what it takes for this town. Because it has to be solved.”

If you have any information about Donna’s case, or, if you can identify the man by name wearing dark pants and the backpack in the Ring video, call Galveston police at

409-765-3702.

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious crime after 40 years

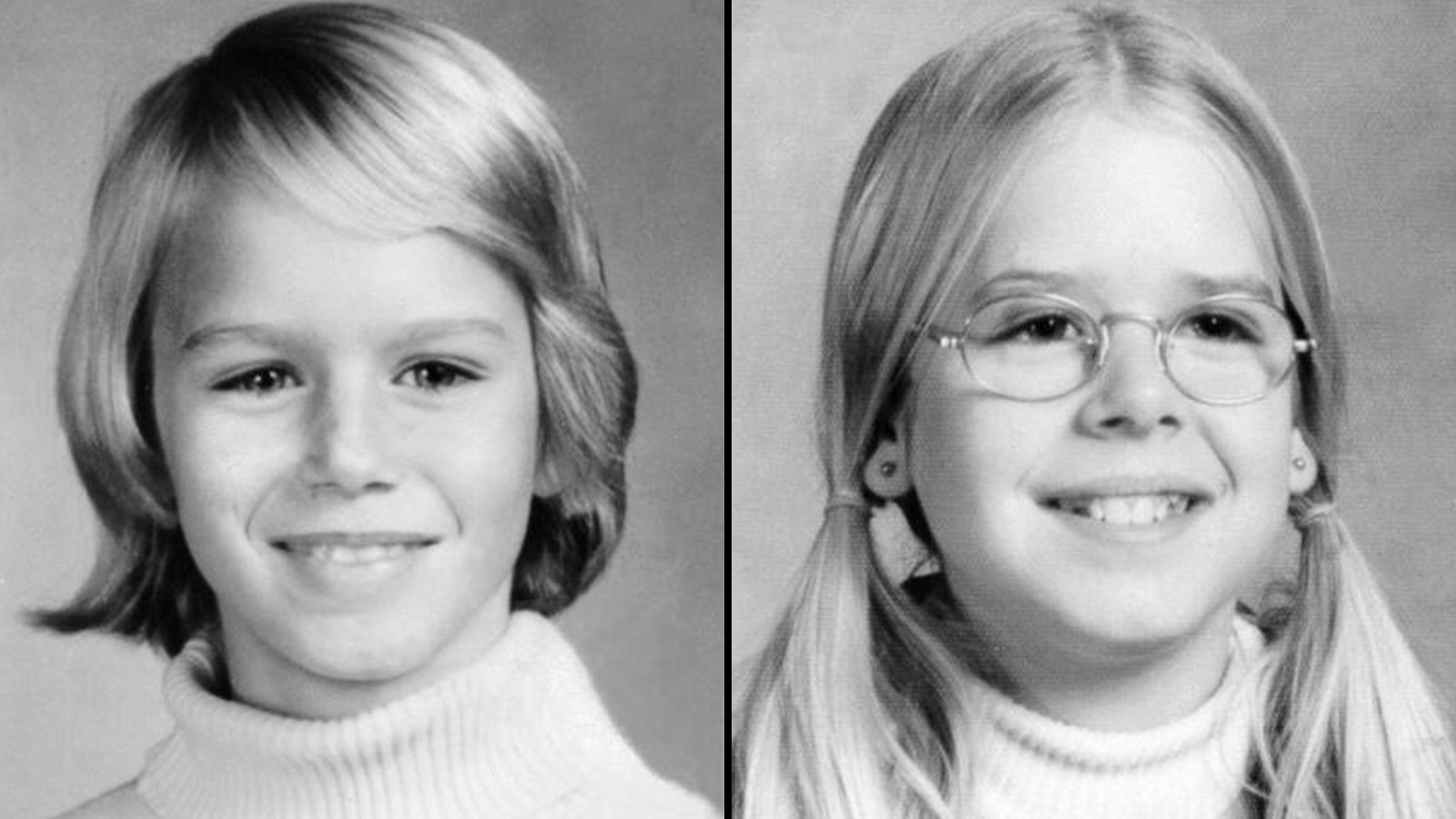

For decades, the disappearance of Sheila and Kate Lyon wasn’t just an enduring mystery; it was an unhealed regional trauma. On a March day in 1975, the sisters — daughters of a well-known Washington radio personality — had gone to Wheaton Plaza, a suburban Maryland shopping mall, on an innocent outing, and then vanished. They were never seen again, though the hunt for them was relentless and extensive. Police interviewed countless witnesses and followed hundreds of tips. Every stand of woods or weeds was searched. Storm sewers were explored, as was every vacant house for miles. The residents of a nearby nursing home were interviewed, one by one. Scuba divers groped through mud at the bottoms of ponds. Nothing was found. Nothing came of anything the police did.

I was a green 23-year-old reporter with the Baltimore News-American when the story broke. My job was to show up in the newsroom at 4 a.m. and phone every police barracks in the state, asking whether anything interesting had happened overnight.

When, on the morning of March 26, the desk officer in Wheaton told me about the missing children, I drove directly to the scene. This was a story that was sure to attract attention. Millions of families in the region lived in neighborhoods just like the Lyons’ in Kensington, Md., shooing their kids out the door in the morning and catching up with them at mealtimes, unconcerned about where they went. A story like this struck at suburbia’s idea of itself.

My first story ran two days after the girls vanished, under the headline “100 Searching Woods for 2 Missing Girls.” It had photos of 12-year-old Sheila, in blond pigtails and glasses, and 10-year-old Kate, with her blond hair cut in a cute bob. As days passed with no good news, the tale turned grimmer. In my newspaper the story was still on the front page at the end of the week: “Hope Fades in Search for Girls.” But in time, as nothing happened, the story moved off the front page and then out of the news completely, overtaken by fresh outrages.

As the decades passed I wrote thousands more stories, big ones and small ones. I raised five children of my own. I became a grandfather — of two little blond-haired girls, as a matter of fact. To me, the Lyon story was sad and beyond understanding. Few haunted me as this one did.

While today we can all too readily imagine the disappearance of a child, in 1975 it was shocking — and all the more so because it was two children. Imagining how or why it happened was difficult. The problem of controlling two alarmed children suggested more than one kidnapper, which raised the question, why? What would motivate two people or a group? A sex-trafficking ring? A circle of pedophiles? Just speculating about it conjured scenarios that made you ashamed to be human.

The case haunted the Montgomery County Police Department, too. It was a pebble in the department’s shoe. Generations of detectives had come and gone, and many had taken a crack at it. Periodically, a new team would start over, combing through the many boxes of yellowing evidence, hoping to find something missed. This is what cold case teams do. They embrace the tedium. They are the turners of last stones, laboring in a landscape beyond hope.

But just as the most recent team was preparing to give up, a ray of hope emerged. Detective Chris Homrock stumbled upon a file he had never seen before — the six-page transcript of a statement by an 18-year-old named Lloyd Lee Welch.

On April 1, 1975, Welch, a long-haired drifter with drug and alcohol problems, had contacted Montgomery County police to say that he had witnessed the Lyon sisters’ abduction. Officers had dismissed his elaborate, overly detailed account as a lie, an attempt to insinuate himself into the story, play the hero and collect a reward. But nearly 40 years later, the cold case squad wondered if he really had seen something. At the end of his statement, he had said that the kidnapper walked with a limp, as did the man the detectives, at the time, considered their top suspect. They found Welch in Delaware, at the tail end of a 33-year prison term for molesting a 10-year-old girl, a fact that further piqued their interest.

On Oct. 16, 2013, Detective Dave Davis traveled with Homrock and Montgomery Deputy State’s Attorney Pete Feeney to Dover, Del., to interview Welch, who stunned Dave with the first words out of his mouth. “I know why you’re here,” he said with a sly grin. “You’re here about those two missing kids.”

Related

Six black girls were brutally murdered in the early ’70s. Why was this case never solved?

Lloyd was nothing at all like the reticent man FBI analysts had led the detectives to expect. He appeared to enjoy talking for its own sake, and even though he knew Dave was working on the old Lyon case, he seemed indifferent to the risk. He talked like a man addicted to talk, free-associating, and Dave, who had worried about how to get him going, just sat back and listened.

In that first session, Lloyd denied any involvement with the Lyon girls’ disappearance. “I didn’t kill anybody,” he told Dave. “I didn’t rape anybody. I didn’t do nothin’ to those girls. I mean, I really don’t have much to tell.”

But he went on talking. And after a full day of interrogation, he let slip something that caught the detectives’ attention. The squad had been working on the assumption that Lloyd had witnessed — or possibly assisted in — the girls’ abduction by a pedophile named Ray Mileski. Wrapping up the session, Dave made a final stab at getting Lloyd to reveal something.

“All right, I think they’re, we’re pretty much done,” he said. “But what I wanted to ask — your opinion only — what do you think [Mileski] did to those girls?”

“Personally?” Lloyd asked.

“Yeah, I’m asking you for an opinion.”

“Well, my opinion is that he killed ’em and raped ’em; he killed ’em and he probably burned ’em. I don’t know.”

In the adjacent room, Chris and Pete looked at each other. “Who says ‘burned them’?” asked Pete.

In subsequent sessions with Davis and Homrock, and later also detectives Katie Leggett and Mark Janney, Welch lied elaborately and repeatedly about his connection to the Lyon case. He eventually admitted that he had helped kidnap the girls but insisted that the crime had been planned and carried out by others in his family — first naming a cousin, then an uncle, then his father, who he said had abused him sexually as a child.

In the summer of 2014, the squad began an extensive probe of the entire Welch clan. What the detectives found shocked them. The clan had two branches, one in Hyattsville, Md., and the other five hours southwest, on a secluded hilltop in Thaxton, Va., a place the locals called Taylor’s Mountain. Here the family’s Appalachian roots were extant, even though some members had gradually moved into more modern communities in and around Bedford, the nearest town. While its environs were markedly different, the branch in Maryland clearly belonged to the same tree.

The family’s mountain-hollow ways — suspicion of outsiders, an unruly contempt for authority of any kind, stubborn poverty, a knee-jerk resort to violence — set it perpetually at odds with mainstream suburbia. Most shocking were its sexual practices. Incest was notorious in the families of the hollers of Appalachia, where isolation and privation eroded social taboos. The practice came north with the family to Hyattsville. Here, where suburban families took child-rearing seriously, some adults in Lloyd’s immediate family exploited their offspring and ignored barriers to incest. It was not uncommon for Welch children to experiment sexually with siblings and cousins. If the Lyon sisters had fallen into this cesspool, as Lloyd claimed and the detectives now suspected, then some of the family might have known — and even helped.

At this point, Lloyd was claiming that the chief culprit had been his Uncle Dick, who he said had planned the girls’ kidnapping and then presided over their gang rape, murder and dismemberment. Wiry, flinty and truculent, Dick Welch was nearly 70 but seemed older. In addition to heart trouble, he faced a frightening array of accusations. Various family members had accused him of ugly and violent behavior toward them in the past.

Dick denied it all; he said little, and what he did say was simple and consistent. Indeed, he behaved like someone wrongly accused, bewildered and frustrated by wounding falsehoods. He was summoned to appear before a grand jury in February 2015. When the prosecutor asked him whether he’d had any involvement in the Lyon case, Dick was succinct and firm.

“God as my witness, no.”

“Did you transport one or both of these girls — Sheila and Kate Lyon — from Wheaton Plaza to your residence?”

“No, I didn’t. I’ve never been there.”

“Did you have sexual contact with either Sheila or Kate Lyon?”

“God as my witness, no.”

“Do you have knowledge of any of these things that I’ve talked about?”

“No, but I wish I did.” He had earlier said that he wished he could help the detectives solve the mystery.

“Do you have any explanation why people would say that you did?”

“I don’t know why I’m getting accused, them saying I did this, I done that. I haven’t.”

Pat, Dick’s wife, would eventually be charged with organizing family efforts to stonewall the investigation. Lloyd’s cousin Teddy Welch, the first family member he named as the girls’ kidnapper — though Teddy was only 11 in March 1975 — had run off as a boy to live with a middle-aged man. Two other cousins, Henry Parker and his sister, Connie Parker Akers, still lived near the family homestead on Taylor’s Mountain. Both would prove to be helpful, if reluctant, witnesses to the strange burning of a bloody duffel bag in a bonfire on Taylor’s Mountain, delivered there by Lloyd. Each of these family members and many others told ugly stories of being either victims or witnesses to inter-family sexual assaults.

loyd had emerged from this culture as both victim and predator. After years of wandering and imprisonment, he had strayed far from the family’s grip, but the peculiar values and behavior he had learned (and endured) had not played well in society at large.

By early 2015, the detectives had formed a much fuller picture of Lloyd in 1975. They could look past the sad, pasty, wily, shackled old man who met them in the interview room and see teenage Lloyd: lean, dirty, mean and high. In ordinary times, this might have made him stand out, but in the late 1960s, many teenage boys were growing their hair long, dressing shabbily, infrequently bathing, and experimenting with drugs. For most, this period was a fling. But for Lloyd it was no pose. He really was poor, desperate, dirty and up for anything.

By 1975 the hippie movement had faded, but Lloyd hadn’t changed. He was then part of a class of shaggy vagabonds thumbing their way around the country on back roads, camping in the woods outside suburbia.

Like Lloyd and his girlfriend, Helen, many were heavy drug users. They still proclaimed the fading mantras of the hippie moment — free love, mind-expanding drugs and the all-encompassing “If it feels good, do it” — but few had considered what such a credo might mean to a man like Lloyd Welch.

At 18 he was already an outlaw, stranded on the fringes of a prosperous world beyond his grasp. Shopping malls then were suburbia’s gleaming showcases, lined with high-end stores stocked with goods Lloyd could not afford. And while he was not the sort to reflect on such things, he must have resented the plenitude, all the comforts of money, family and community that he lacked. As Lloyd himself had put it, “I was an angry person when I was young.” And if he felt scorn, or rage, how better to strike back than to stalk the very thing the mall’s privileged customers most prized? The pretty little girls he saw there, to whom he was perversely attracted, represented everything he was denied. Might a man like this have abducted and killed the Lyon sisters?

The detectives came to realize that you had to forget the narrative. The way to read Lloyd was to look past his stories to their details.

Lloyd continued spinning one story after the next to explain what had happened to Sheila and Kate, always placing the blame for the crime on others. But gradually — often inadvertently — he revealed more and more about himself and the crime.

The detectives came to realize that you had to forget the narrative. The way to read Lloyd was to look past his stories to their details. Running through many of his versions were certain particulars that recurred: stalking girls in the mall, an offer to get high, a station wagon, a crying girl in the back seat, a basement hangout accessed from the backyard, rape, drugged girls, a pool room, an ax, the girls “chopped up” and “burned,” an Army green duffel bag, a bonfire. As if in an ever-churning blender, these stubborn nubs kept surfacing. The more they surfaced, the more they began to look true.

On a Monday in May 2015, Dave Davis went looking for the place where Lloyd said Dick had killed and dismembered Kate before stuffing her remains in a duffel bag and ordering Lloyd to take it to Taylor’s Mountain and burn it. It was a secluded spot under a bridge near his uncle’s old home in Hyattsville. Dick went there to fish and drink and smoke. It was his “comfort area.” Lloyd was “90 percent” sure about it.

Dick’s old house had been razed to make room for a new district court building. But Dave knew where it had been, and he went there first.

Right away, Lloyd’s story didn’t add up. The house was the last place you would choose to bring two little girls who were the object of a bicounty manhunt. Even back in the 1970s, before the new courthouse, the address had been a stone’s throw from the city’s police headquarters. There were officers coming and going all the time.

Lloyd had said that there were railroad tracks behind the house and that the bridge over the Anacostia River was a short distance from the front door. But the tracks were in front of the house, not behind, and across Rhode Island Avenue. The river, which was more like a creek, was not even close. The map showed it four blocks east. The layout was nothing like the one Lloyd had described.

Dave next sought out Buchanan Street, which Lloyd had also mentioned and where members of the Welch family had once lived. It was not far away, running southeast from Baltimore Avenue down to the river basin. Dave drove along that route to a dead end that looked down to the water. To the left was a rail bridge that angled across it.

Dave climbed the low fence and walked down to the water. This was clearly the place Lloyd had described, but it was no secluded haven; the angle of the bridge exposed it to views from neighborhoods all around. With all the dealerships and parking lots in the vicinity, it would have been well lit at night. It was like being onstage in a theater-in-the-round. Another Lloyd Welch curveball.

Dave had begun to lose hope of ever sorting out what had happened to the girls. But as he drove back up Buchanan, staring him right in the face across busy Baltimore Avenue was a house he recognized from snapshots in the file. It was the house where Lloyd’s father, Lee, and his wife, Edna, had lived, 4714 Baltimore Ave., a two-story, white-clapboard duplex with pale blue trim and an uneven front porch. This was the address Lloyd had given when he’d made his original false statement. Lloyd had described seeing his uncle pull out of a driveway with the Lyon sisters in his car, heading toward the river — this now made more sense. The location fit Lloyd’s description perfectly, once you saw that it was not his uncle’s house but his father’s.

It struck Dave with the force of revelation. Just as Lloyd always moved himself off-center in his stories, so he had moved this house. The detective pulled over, crossed Baltimore Avenue, and knocked on the front door.

A friendly Hispanic woman who spoke almost no English answered. Dave managed to make himself understood enough to say that he wanted to look at the basement. She showed him that there was no way to enter it through the house. You had to go outside, down the porch, and along the driveway to the backyard, where steps led down to a padlocked door. In every scenario Lloyd had spun, there was a basement hangout, a place where the girls had been kept. He had placed it first in Teddy’s older friend’s home, then in his uncle Dick’s, but in both it was a room that could be entered only by walking around the house to the rear. Once Dave understood how Lloyd’s mind worked, he knew, without question, this had to be the place.

Dave jiggled the latch, and the door opened. He stepped into a dark, low-ceilinged stone dungeon heaped with old furniture. It was so hauntingly familiar it raised the fine hairs on the back of his neck. This was the place. He knew it. It was exactly where one would stash two stolen, frightened, drugged little girls — two rooms completely cut off from the house above. You could do whatever you wished in this space without being seen or heard.

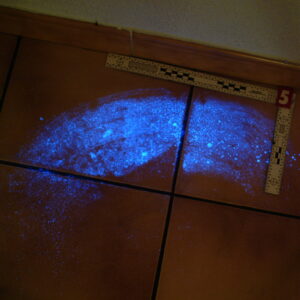

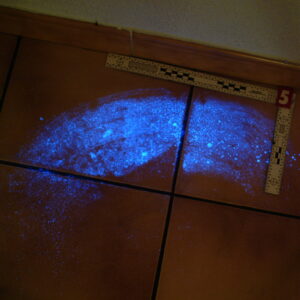

Dave returned the next day with a forensics team. They cleared away some of the old furniture and started squirting Bluestar spray, a blood-detection agent that bonds with even the slightest trace of hemoglobin and glows brightly under a blue light. The floors and walls of the outer room revealed nothing much. Then they cleared debris from the back room and sprayed some more. It lit up from floor to ceiling. It lit up like a murder scene. Someone or something had been slaughtered in this room.

And then Dave knew. All uncertainty vanished. He was even more certain because he had not been led there by Lloyd; he had found it himself. He had extracted it from Lloyd’s stories, bit by bit.

Aglow in blue light, the room announced itself as the place where Sheila and Kate Lyon, lured from Wheaton Plaza, had been drugged, raped and imprisoned, and where at least one of them had been killed and dismembered. Before he had switched the location to a bridge, Lloyd had talked a lot about a basement hangout, his Uncle Dickie’s sanctuary, a place with a locked door, where Dick went to smoke and drink. But it wasn’t Dickie’s basement. It was the basement of Lee’s house, where Lloyd had been living, the space where Lloyd hung out, smoked dope, drank and “partied.” It was his.

Not long after Dave Davis found the likely murder scene, the case against Lloyd was solid enough to charge him with the crime. Whatever illusions he may have had about winning his long-running game with the Lyon Squad were dashed. On Sept. 12, 2017, he pleaded guilty to two counts of felony murder in a Bedford courtroom. Though he still denied that he had raped or killed the sisters, his admission fell well within the confines of a Virginia legal doctrine defining as murder a killing “in the commission of abduction with intent to defile.” He was indicted in the commonwealth because the case against him was stronger there, his cousins having corroborated his final story of driving human remains to Taylor’s Mountain. Lloyd had also several times voiced his fear of execution, so he was considered more likely to accept a guilty plea in Virginia, a death-penalty state — a calculation that proved correct.

The plea spared him from death row, but he would almost certainly never leave prison. His sentence was 48 years. He was 60 years old, and he had, from first to last, talked himself into this outcome.

Although details about their fate — how precisely Lloyd had enticed the girls and what had happened to Sheila — and who exactly was involved remained unsolved, Lloyd’s plea answered my deepest questions: Who would commit such a crime? And why? But I wanted to meet Lloyd Welch. I wanted to size him up for myself, and I also wanted to close the book on the mystery that had been with me my entire professional life. I wrote him a letter requesting an interview and was surprised when he wrote back immediately, saying he would agree to be interviewed if I put $5,000 in his prison account and met certain other terms. I would not meet any of them but offered to discuss them in person.

Sitting directly across from Lloyd felt familiar; I had watched him on video in the interview room for more than 70 hours. He looked thinner than I expected, with a pale pink complexion, and his watery slate-blue eyes were magnified behind his glasses. He was cordial but all business. If I was expecting to look evil in the eye, I was disappointed. What I found was an unimpressive, scheming man, capable of charm but only to the extent that it served his interest, someone natively bright but deeply ignorant and cocky beyond all reason.

If I was expecting to look evil in the eye, I was disappointed. What I found was an unimpressive, scheming man, capable of charm but only to the extent that it served his interest.

He displayed his usual poor sense of situation, believing he had a lot more leverage over me than he did. The terms he repeated were ridiculous, but I heard him out. Then I asked the questions I most wanted him to answer.

“Why did you keep talking to the detectives?”

Lloyd said he had no choice. He said his repeated requests for a lawyer were ignored. Prison authorities told him that he had to continue meeting with the detectives. None of this was borne out by the videos I had watched. His participation throughout had appeared completely voluntary.

Dave Davis had asked me to convey a message. I was to assure Lloyd that his prison account would never be empty if he revealed where the girls’ bodies were. It wasn’t an official offer, but the Montgomery County police had spent millions on the investigation and still didn’t have that answer.

“I have told them all I know,” Lloyd insisted. “Just because a person pleads guilty to something doesn’t mean they are guilty of it. I did not murder or kidnap them girls.”

Who did?

His Uncle Dick was responsible.

“How do you think I would take two little girls out of the mall, kicking and screaming?” he asked. “Who would be able to do something like that? A man with a uniform.” (Dick had worked as a security guard.) He didn’t understand why Dick had not been charged. He said he was afraid of his uncle, as he had been in 1975.

While insisting on his innocence, Lloyd nevertheless seemed a little proud of whatever role he had played in the crime. I told him of my early coverage of the story, and of all the years I had wondered about it. He noted that it had taken the Montgomery County police almost 40 years to link him to the case. “I’ll bet it seemed like the perfect crime, didn’t it?” he boasted.

He complained about being treated as a rapist and child-murderer in the prison. Someone, he said, might still “put a shank” in his back. Then he said he had enjoyed the interview sessions because they got him out of the prison, and he got to eat something better than prison fare. “That’s one of the reasons I kept talking to them,” he said, contradicting what he’d said minutes earlier. He insisted that he had told the detectives the truth throughout, only sparingly. “I was also trying to protect myself.”

By the end of our appointed hour, I saw no strong reason to talk with him further. I had seen him invent and reinvent his version of the story so often that I saw no point in inviting him to do the same with me. But when I wrote back to him a few days later to reject his deal, I added that if he changed his mind about the payment and wanted to talk with me more, I’d come back and listen.

I got another letter from him promptly. “I received your letter and I am very disappointed in this. So let me say this to you so you can understand what I am saying to you. First the documentary you are doing, you may not use any pictures of me or Helen and you may not use my name in anyway at all. … Now, as for your book, I do not give you any permission to use my or any pictures of me or Helen in any way. You do not have my approval or authorization to use anything about the Welch’s name. You may not use any of the interview sessions that you have of me.”

He continued, “Sorry we did not come to some kind of a understanding. … If you want to come see me then you will have to put $300 on my commissary’s books before you can talk to me again. My time is money now.” I noticed that, despite his tone, the price had dropped considerably.

Mark Bowden is an award-winning journalist and author. This article is adapted from his most recent book, “The Last Stone: A Masterpiece of Criminal Interrogation,” published this month by Atlantic Monthly Press.

Credits: Story by Mark Bowden

Subscribe to our newsletter

Year

Country

Archives

- July 2023

- March 2023

- September 2022

- April 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- May 2017

- March 2017

- August 2016

- July 2016

- January 2016

- June 2015

- July 2014

- March 2014

- September 2013

- June 2013

- December 2010

- June 2010

- January 2010

- March 2009

- March 2008

- September 2007

- July 2006

- August 2005

Forensic PSA Test: BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA® – The Essential Tool for Crime Scene

Forensic PSA Test: “BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA®” An Essential Tool in Forensic Medicine for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Detection In the world of forensic medicine, speed and accuracy

Rose Petal Murder: The Case Involves the Use of BLUESTAR® Forensic Reagent

The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina is drawing national attention and …

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into evidence, they cleared the floor in order to apply a chemical known as Bluestar, which

KU Leuven Students Investigate Virtual Crime Scenes

Investigating murders as a forensic expert… (India Education : Apr 26, 2022) Taking DNA samples, making blood traces visible with a chemiluminescent spray (‘Bluestar’) or

Forensics, the latest methods

When pollen and insect larvae are used to solve criminal cases and even historical enigmas… This documentary takes a look at the fascinating resources of

How does the scientific police work?

How does the scientific police work?(Le Mag de France Bleu Poitou) Television loves forensics, because there are crimes, investigations, motives, and we get to see

Forensic science, clue hunters

Tarbes: Scientific police, the clue hunters La nouvelle république des Pyrénées : November 4, 2021 The technical and scientific police of Tarbes opened us the

Lemerle case: traces of blood revealed by Bluestar

On the first day of Vanessa Lemerle’s trial for the violent confinement of her brother Le quotidien : October 26, 2021 On the first day

A state-of-the-art portable crime lab

Costa Rica’s First Female Forensic Biologist Designed a State-of-the-Art Portable Crime Lab MENAFN : 18.09.2021 In 2010 Tatiana López had to present a University project, she was

“With the blood in the eye” Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials.

“With blood in the eye”. Romano et al. Axis 1 – Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials. Presentation of the paper “With blood in the eye”. Revealing and

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches Neither cadaver dog made strong alerts to seized Volkswagon or Ruben Flores’s property

Troadec case: traces of blood, burning of the bodies, the word of the experts.

The trial of Hubert Caouissin and Lydie Troadec continued with the testimony of experts who worked on the case. France info : 29.06.2021 The trial

Alleged serial killer: new excavations and Bluestar in the orchard

Could the crime scene at Mare-d’Albert be hiding other sordid secrets? In any case, this case, which has been in the news since Friday 28

Police brought Agostina’s alleged femicide to Neuquén

A commission of the local police force transferred Juan Carlos Monsalve from Viedma, accused of being the perpetrator of the femicide. Agustín Martínez LMCipolletti :

Detecting Blood in an Outdoor Environment with the Bluestar Reagent and DNA Analysis

Author(s): McCall, Keenan; Woods, Grace; Richards, Elizabeth Type: Article Published: 2021, Volume 71, Issue 4, Page 309 Abstract: Blood is an important physical material that

Thomas Lesire trial: These clothes are examined with Bluestar reagent

Assizes: trial of Thomas Lesire, accused of the murder of an octogenarian in Châtelet, begins RTBF 03.05.2021 The neighbourhood investigation led the police to a

Daval case: investigation and use of Bluestar

Daval trial: life sentence requested against Jonathann Daval accused of a “terrible” crime, relive the sixth morning of the trial L’est Républicain : 21.11.2020 “When

Case of a missing youth: raids and investigation procedures continue

The procedure was carried out jointly with police personnel from the Forensic Science Department and the 43rd Central Police Station of Jhugua Ñaro and the

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years ABC 13 : 29.06.2020 [United-States/Texas] Donna Brown walked into the Alcoholics Anonymous building

He had tried to erase the trace of the victim’s blood

The baby was beaten and tortured, recorded in bruises, scratches, burns and fractures from the brain down. Photo: Jenny Rocio Angarita Galindo (Radio RCN) Alerta

Policeman’s Memory : a barbaric crime!

By Fadel ATAALLAH – POLICE magazine N° 57 Octobre 2009 This article reports on a criminal case solved by senior police officer Abdelmoula Choukrallah, head

Narumi case: investigators accuse the main suspect

The Chilean ex-boyfriend of this Japanese student who disappeared in Besançon in 2016 fled to his country. The French justice has just revealed accusing elements

Christine Wood’s DNA found in Brett Overby’s basement, court says

CBC NEWS : 02.05.2019 Christine Wood’s blood was found on a weight bench, closet door and stairs in the basement of a Burrows Avenue home

Bluestar, the miracle product that solves many criminal investigations

Bluestar, which was developed in a CNRS laboratory, has become an essential tool in complex investigations and a formidable weapon in the hands of the

Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious crime after 40 years For decades, the disappearance of Sheila and Kate Lyon wasn’t just

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Murder of a woman by her son

This matricide was solved by the French Gendarmerie Nationale using BLUESTAR® FORENSIC. The woman had been missing for 15 days. BLUESTAR® FORENSIC was sprayed in

Alexia Daval case: other acts and hearings to come

L’est Républicain : 07.07.2018 New forensic expertsAbout forty experts of all kinds have already worked on the case: no less than five forensic doctors; several

JESSIE BARDWELL CASE: WAS TEXAS WOMAN’S DEATH AN ACCIDENT OR MURDER?

A father dreams his daughter has been killed, then she disappears — what does her boyfriend know and could the dad’s nightmare have been an

They capture the partner of a mannequin

The subject claimed that when he arrived at the apartment he found the woman dead, but technical evidence contradicts this version and indicates that he

Scientific advances have made a blood trail speak for itself

Maëlys: how scientific progress made a microscopic trace of blood talk FRANCE 3 : 09.12.2019 They escaped the meticulous cleaning of Nordahl Lelandais. Then, at

Invisible bloodstains revealed by Bluestar

Mallouk case: the long trial of a murder without a confession (FRANCE 3) Hafid Mallouk is to be tried for a fortnight for the murder

A matter of gold and blood

BEHIND THE DISAPPEARANCES OF ORVAULT, THE TROADECS’ FAMILY TRAGEDY (France Info story) A blue and white column slowly progresses through a wooded and soggy landscape.

Killer of elderly woman confesses he had help from hitman

Puno: the killer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman Diario Correo : 27.05.2017 He killed his wife because he

The murderer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman

Puno: the murderer of an old lady confessed having been helped by a hired killer Diario Correo : 27.05.2017 He killed his wife because he

The scene of a crime, suicide or natural death has no mystery for the “cleaners”

It’s a job that is rarely mentioned, as if to ward off bad luck. The very mention of it brings to mind crime scenes seen

Improved detection of Luminol blood in forensics

Review: Improving Luminol Blood Detection in Forensics Florida Forensic Science : 01.03.2017 (Emily C. Lennert) Article to be reviewed: 1. Stoica, B. A. ; Bunescu,

Officers get forensics training

A couple dozen first responders and crime scene investigators gathered around a makeshift crime scene Wednesday afternoon in Jackson. Jackson Sun : 31.12.2016 They watched

Photographing bloodstains

Photographing bloodstains: Bluestar reagent FORENSICS 4 AFRICA 07.07.2016 (Nick Olivier) In the late summer of 2012, police officers in a small Midwestern town were called

Mystery around a disappearance

Yves Bourgade’s murder: BLUESTAR® FORENSIC strengthens suspicions about his wife…

Nisman case: the conclusions of the criminal report

Nisman case: conclusions of the official criminal report point to suicide 11.06.2015 – ARGENTINE – INFOBAE – Infobae has accessed the 97-page document that

Traces of blood were found in his marital home, revealed by the “Bluestar”.

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on telegram Share

The judge in the Yexeira case accepts as evidence another piece with blood on it.

To complete the process of authenticating the evidence, the magistrate noted that the other ICF staff member who received the evidence for analysis would also

20 years of forensic bloodstain analysis in Ontario

While University of Windsor students play with spatter at a forensics conference, provincial police mark the 20th anniversary of bloodstain pattern analysis in Ontario. (Dax

Chief Warrant Officer Benitez left a bloody trail

The clues are accumulating around Chief Warrant Officer Benitez and his involvement in the disappearance of Allison and her mother Marie-Josée on 14 July in

El suboficial mayor Benítez dejó un rastro sangriento

Las pistas se acumulan en torno al suboficial mayor Benítez y su implicación en la desaparición de Allison y su madre Marie-Josée el 14 de

L’adjudant-chef Benitez a laissé un sillage sanglant

Les indices s’accumulent autour de l’adjudant-chef Benitez et de son implication dans la disparition d’Allison et de sa mère Marie-Josée, le 14 juillet à Perpignan.

The Flactif case: An investigation solved with Bluestar

At a crime scene, he makes the bloodstains talk “When I entered the Flactif house, I immediately noticed the traces of sponge strokes in the

Photographer Exposes Crime Scenes, With a Dash of Chemistry

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on skype Share

Bloody gloves in Israël

Bloody gloves “catch” Israeli attorney Anat Plinner’s murderer…

Forensics, how does it work?

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on pinterest Share on reddit Share on vk Share on tumblr Share on skype Share

Flactif, The cursed cottage is for sale

The parents of Xavier Flactif, massacred with his family in April 2003, have returned to the scene of the tragedy. The chalet of Grand-Bornand, in

The blood of two confederate soldiers revealed at Gettysburg

Gettysburg Civil War case revealed after 142 years !

Suspect arrested on crime scene after his arms turn blue !

A man arrested after his arms turn blue…

The secrets of real experts (LE FIGARO)

Philippe Esperança, morpho-analyst: Blood on the trail By Le Figaro, 21/07/2006. “Espé” is the French specialist in the revelation and analysis of bloodstains. At the

The Flactif case: With Philippe Esperança

BLUESTAR® FORENSIC helped solve the Grand-Bornand quintuple murder case The Flactif family had mysteriously disappeared from their chalet. The programmes “Faites entrer l’accusé” and “Secrets

Shooting of a pedestrian by a driver

A driver shoots and kills a pedestrian…

JESSIE BARDWELL CASE: WAS TEXAS WOMAN’S DEATH AN ACCIDENT OR MURDER?

A father dreams his daughter has been killed, then she disappears -- what does her boyfriend know and could the dad's nightmare have been an omen?

CBS NEWS : 23.06.2018

Jessie Bardwell, 27, a beloved daughter and friend seemingly vanished from the Texas home she shared with her boyfriend, Jason Lowe. Fearing the worst, her father traveled from Mississippi to Texas to start the search for his daughter. Jessie’s body was later found in a remote spot of farmland wrapped in a sheet.

Jessie Bardwell GARY BARDWELL

Police suspected murder, but was it?

“This story is about a young girl,” Richardson, Texas. Detective Eric Willadsen tells “48 Hours” correspondent Maureen Maher. “Thinks she finds love and it turns out he’s pure evil.”

Jessie was fun-loving and outgoing, say friends and family. She lived in Orange Beach, Ala., where she worked at a local hotspot.

Then she fell for Lowe. To the surprise of her family, one day she moved to Texas. Turned out she was following Lowe, who had landed a job in Dallas. She suddenly disappeared in May 2016.

“I knew she was dead,” Jessie’s father, Gary Bardwell, tells Maher.

Bardwell said he had nightmare before his daughter disappeared. “Something was terribly wrong. Jessie was … was killed. …And when I woke up, it was just a dream.”

“And I felt it – she was not on this earth anymore,” he says.

Gary Bardwell immediately filed a missing person’s report. After multiple visits to Jason and Jessie’s home, detectives had a sense something was wrong. There were things out of place and the unmistakable scent of death. Soon after, Lowe was arrested and charged with murder.

Lowe later claimed Bardwell’s death was an accident. His attorney had a plan, and he put together a mock trial to test the defense theory. The result of the stand-in jury? Lowe was not guilty. Prosecutors, however, maintain it was murder and Lowe tried to hide her body.

“I think about what I think happened to her. And I couldn’t protect her,” Bardwell tells Maher. “It’s just unimaginable. It’s unthinkable. It’s unforgivable.”

What happened to Jessie Bardwell?

A GUT FEELING

Gary Bardwell: Yesterday — I went down to the river and just — set there and watched the boats go by and took some deep breaths and said, I don’t know how much of this I can take, you know, any longer.

There are days when it’s hard for Gary Bardwell to get out of bed. But he always does, determined to get justice for Jessie, his 27-year old daughter who disappeared from her apartment in Richardson, Texas, in May 2016.

Gary Bardwell: I’m doin’ it for Jessie, takin’ one day at a time, one step at a time.

Bardwell knew something was wrong before he even knew Jessie had gone missing.

Gary Bardwell: Somethin’ from my soul was gone. And I was afraid that it was her.

“I called her my beautiful daughter. And I still do. Beautiful Jessie,” said her father, Gary Bardwell GARY BARDWELL

That connection, that bond deeper than words, formed the moment Jessie was born, says Bardwell.

Gary Bardwell: As soon as she was born I immediately started crying. …It was just such a happy moment — such a happy moment.

Jessie grew up alongside her older brother, Brandon.

Brandon Bardwell: Me and Jessie have been two peas in a pod since we were young.

Gary Bardwell, a now-retired firefighter with the Pascagoula, Mississippi, Fire Department, loved being a dad.

Gary Bardwell: She kinda didn’t want me out of her sight … She just liked to know where I was.

[Holds Jessie’s teddy bear] She slept with this every night.Gary Bardwell: I just loved those days.

Gary Bardwell: Daddy’s little girl, for sure.

When Jessie was 14, Gary and her mother, Carla, divorced.

Gary Bardwell: She loved her mother too. …Very much so.

Jessie spent her high school years with her father and her new stepmother, Gina.

There were a few tries at college life.

Gary Bardwell: Somewhere along the line, she was having more fun than school.

That’s when Jessie moved to Orange Beach and started working tables at Cobalt, a popular beachside restaurant.

Gary Bardwell: She just loved being around the water …. She would be in the water fighting the waves and having fun.

Gary Bardwell: We talked every day. She’d text me every day.

Jessie’s good friend, restaurant manager Kimberly Asbury found out Gary Bardwell was an accomplished musician, and booked him at the restaurant.

Kimberly Asbury: Like he came and they went boating and they went fishing … She’d go to his gigs. I mean they were friends. They weren’t just father and daughter.

Jessie had been living with a long-term boyfriend, but surprised everyone when she fell for a new guy, Jason Lowe.

Kimberly Asbury: It kind of came out of nowhere.

Jessie’s friend Terri Ellis saw the romance start.

Terri Ellis: Jason seemed friendly. …He definitely — was outgoing as well.

Jason Lowe FACEBOOK

He was handsome, had two college degrees and was ambitious. For Jessie, not just a new love - but a ticket to a more exciting life. When Jason went to Dallas for a six-figure job in the tech industry, Jessie decided she would join him and pursue her own dream of cosmetology.

Terri Ellis: She thought of it as more of an adventure. Like,” I’m trying something new.”

But Jessie failed to mention that she was about to go to Dallas when she saw her family that Christmas.

Gary Bardwell: I had no clue of what was going on.

Gary Bardwell: She knew that she was fixing to leave for Texas and I would have done everything I could to try to talk her out of it.

Shortly after the holidays, Jessie left for Texas. And suddenly the girl who always had her iPhone was now never on it.

Kimberly Asbury: You couldn’t reach her.

Kimberly Asbury: It just went from hearing from her a lot and talking to her to nothing.

Terri Ellis: The moment that I really started to get worried was when her phone number was cut off and everything that we talked to her had to go through Jason.

The only way to get Jessie was to call Jason’s phone or the house phone. They would come to find out that Jason was monitoring all her calls. Eventually, every time Bardwell called Jessie, he only got Jason.

Gary Bardwell: I said, “Let me speak to Jessie.” He said, “She said she’ll call you later.”

Two months later, Bardwell finally got his chance to meet Jason Lowe. Jason and Jessie came to Pascagoula for a visit. Bardwell tried to persuade Jessie not to go back to Texas.

Gary Bardwell: I remember Jessie was — huggin’ me more than normal … And I was goin’, “Are you OK?” “Yeah, yeah. I — I definitely wanna go to Texas. I just want you to be proud of me, you know?” …They left. I watched the car drive away.

Even though Jessie never let on that anything was wrong, Bardwell had a bad feeling. He went into his studio — Jessie’s childhood room — and wrote the song, “Taken Away.”

Gary Bardwell: That song, “Taken Away” was written the very last time I saw Jessie. …It was written about seein’ them leave, me gettin’ a gut feelin’ of something was bad wrong.

In May, four months after Jessie moved to Texas, she stopped answering his calls all together. Bardwell called Jason, and insisted on knowing where Jessie was. He says Jason told him he didn’t know.

Maureen Maher: What was he saying?

Gary Bardwell [mimicking Jason’s voice]: “I don’t know where in the hell she is. We don’t live co-dependent … She can go … and come as she pleases.”

But when she didn’t call her mom and stepmom on Mother’s Day, Bardwell had had enough.

Gary Bardwell: I said, “We’re leaving in the morning. Let’s pack some bags. And we’re going to Texas.”

A FATHER'S MISSION

When Gary Bardwell got in his truck and headed to Texas, he was angry. Very angry.

Gary Bardwell: I get so angry that it scares me.

His little girl was missing and he believed Jason Lowe was behind it.

Gary Bardwell: I text him on the way there. I said, “If Jessie’s not there when I get there, you are in a tremendous amount of trouble.”

But when he got to Jessie and Jason’s apartment, she was nowhere to be found. Bardwell immediately filed a missing persons report with the Richardson Police Department. Over the next 24 hours, the police repeatedly visited the apartment and still she never showed up. That’s when Detective Chiron Hale got assigned to the case.

He first made contact with Jason by phone.

Det. Chiron Hale: He stated … the last time he saw her was on May 8th, which was Mother’s Day — that morning at 10:00 a.m. and she left in her Acura.

AUDIO RECORDING:

Det. Chiron Hale: And is that car still gone?

Jason Lowe: Yes.

The next day, Detective Hale, the lead detective, made a house call and made another audio recording:

AUDIO RECORDING:

Det. Chiron Hale: Still haven’t heard from Jessie, right?

Jason Lowe: I haven’t.

By then Jessie had been reported missing for three days.

Det. Chiron Hale: As the father of three girls, I was very determined to get to the bottom of what had happened to Jessie Bardwell.

It seemed everybody was desperate to find Jessie except the man who claimed to be in love with her.

AUDIO RECORDING:

Jason Lowe to Det. Chiron Hale: We just did our own thing, always. I didn’t question her she didn’t question me and it worked.

The detective looked around the apartment and saw no sign of a struggle. Jason stuck to his story that she left home in her Acura.

Jessie Bardwell posing with the Acura that police learned had been sold three weeks before her disappearance.

GARY BARDWELL

There was just one problem with that story. The police learned that Jessie and Jason had sold that Acura three weeks before Jason claimed she drove off in it. They found it in the new owner’s driveway.

Det. Eric Willadsen: Jason’s lies were not very smart. Who would lie about an Acura that had been sold? … it was pretty clear that there was definitely something — going on other than just a missing person.

It became even clearer the following day. A team of detectives including Hale and his partner Eric Willadsen returned to the apartment. They saw what appeared to be a line of cocaine

AUDIO RECORDING:

DETECTIVE: You have coke on the countertop? A line of it? Yes or no.

JASON LOWE: Yes, sir.

But it was an odor coming from the garage that really got their attention.

Det. Eric Willadsen: It’s a smell that you never forget. Once you’ve smelt it, you know instantly when you smell it again.

It was the smell of death. And it was coming from the back of Jason Lowe’s black Audi. Detective Hale opened the hatch door. There was no Jessie Bardwell, but a body had clearly been there.

When police searched the garage, they came across Jason’s Audi. It was covered in mud and the bumper was ripped-off and stuffed inside the car. The thing that stuck out the most to the detectives was the odor emitting from the back hatch of the vehicle. It was the smell of death. COLLIN COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE

Det. Chiron Hale: There was standing fluid in the back hatch. And it smelled like just decaying flesh. …It had front-end damage. It did not have the bumper. The bumper was inside the vehicle … it had a lot of mud on the inside and on the outside.

One explanation was that he had gotten stuck in the mud while searching for Jessie.

Det. Chiron Hale: He still held onto the fact that he did not know where Jessie was.

When the detectives sprayed the luminol-based chemical Bluestar in the Audi, the cargo compartment lit up — indicating the presence of blood. COLLIN COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE

But when they sprayed the chemical Bluestar in the cargo compartment of the Audi, it lit up like crazy – indicating the presence of blood.

Det. Chiron Hale: It pretty much turned into a homicide investigation at that point.

AUDIO RECORDING:

DET. CHIRON HALE: We’re wondering if you wouldn’t mind coming down to the station so we could talk?

JASON LOWE: Like right now?

DET. CHIRON HALE: Yeah.

Jason Lowe was initially arrested on drug charges and thrown in jail. Detectives used the opportunity to further question him on Jesse’s whereabouts.

Det. Eric Willadsen: We spent a long time speaking with him to try to relate to his emotions, his feelings.

DET. HALE TO LOWE: You see this picture? Look at the picture. Jason.

DET. WILLADSEN TO LOWE: The girl you were in love with. The girl that you wanted to marry.

Det. Eric Willadsen: …and nothing seemed to work.

JASON LOWE: Don’t f—ing patronize me.

Det. Eric Willadsen: He didn’t seem to care … He seemed irritated and thought that — we were trying to pin things on him that he hadn’t done.

DET. WILLADSEN: Will you tell me where she’s at.

JASON LOWE: I don’t know any of that, man I’m wrapped up –like I’m good—I’m not going to be accused of stuff and I’m done talking.

Jason Lowe was charged with the murder of Jessie Bardwell RICHARDSON POLICE DEPARTMENT

Even without a body, Jason Lowe was charged with murder.

Det. Eric Willadsen: I had no doubt that he had killed her.

But they did have doubts — grave doubts — that they would ever find Jessie.

Det. Eric Willadsen: Texas is a huge state. We’ve got lots of rivers, lots of lakes, lots of ponds, fields. There are — 100 million different places you could hide a body in Texas.

Back home in Pascagoula, the town rallied around the family.

Kitty Bardwell | Jessie’s grandmother: They had a candlelight vigil at the beach … praying that she’d be found, maybe safe somewhere.

On May 19, almost three weeks after Jessie was last seen alive, they finally got an answer. The police had reason to believe Jessie was on a remote ranch in North Texas. Gary Bardwell says they wouldn’t tell the family how they knew; only that it was a reliable source. Chief Jimmy Spivey called the Bardwell family into the station.

Gary Bardwell: The chief said, “It’s gonna be a bad day for y’all today because we do not expect to find your daughter alive.”

A team of detectives, FBI investigators, and prosecutors made their way to that remote ranch in Farmersville, Texas. They arrived late afternoon and started walking through the fields.

Det. Eric Willadsen: We saw where he had gotten stuck in the mud.

Maureen Maher: You could still see the car parts on the ground?

Det. Chiron Hale: You could.

Det. Eric Willadsen: We found a piece of metal…looked like it was shielding something — kind of a makeshift burial area, and at that point you could start to smell, you know, decaying flesh, so…

Det. Eric Willadsen: …we walked closer. She was covered with a sheet, so you could tell — but you could see the outline of the body under the sheet.

Jessie Bardwell had been crudely wrapped in a blue fitted sheet and covered with a pile of debris, including a red blanket and two red and gold towels.

Maureen Maher: What was the condition of this body?

Det. Eric Willadsen: It’s one of the worst we’ve seen.

It would take seven days to officially identify her body. The medical examiner ruled Jesse’s death a homicide. But her body was so badly decomposed officials could not say how she was murdered.

Against his better judgment, Jessie’s father read the autopsy report.

Gary Bardwell [overcome with emotion]: I felt it was my responsibility as Jessie’s daddy to read the report. …she was brutally murdered. And she was thrown away like a piece of trash … wrapped up in a sheet barely looking like a person.

Gary Bardwell [overcome with emotion]: They sent the hearse to Texas to pick her up and my firemen buddies loaded her into the back of the hearse … This is my life now.

Over 900 people showed up at First United Methodist Church to mourn the death and celebrate the life of 27-year-old Jessie Bardwell.

Kitty Bardwell: If this town could be washed with all the tears that were shed over Jessie, it’d be real clean. We wouldn’t even need for it to rain for the tears that were shed for Jessie.

While the Bardwells spent the next year grieving, a very different looking Jason Lowe was in a McKinney, Texas, jail cell preparing his defense.

Andy Farkas | Defense attorney: One of the key issues in this case is whether or not to have our client testify.

Jason’s court appointed attorney, Andy Farkas, says he is sure that Jason did not murder Jessie. He’s not so sure Jason can convince a jury. But he has a plan.

Other Articles

Forensic PSA Test: BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA® – The Essential Tool for Crime Scene

Forensic PSA Test: “BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA®” An Essential Tool in Forensic Medicine for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Detection In the world of forensic medicine, speed and accuracy

Rose Petal Murder: The Case Involves the Use of BLUESTAR® Forensic Reagent

The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina is drawing national attention and …

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into evidence, they cleared the floor in order to apply a chemical known as Bluestar, which

KU Leuven Students Investigate Virtual Crime Scenes

Investigating murders as a forensic expert… (India Education : Apr 26, 2022) Taking DNA samples, making blood traces visible with a chemiluminescent spray (‘Bluestar’) or

Forensics, the latest methods

When pollen and insect larvae are used to solve criminal cases and even historical enigmas… This documentary takes a look at the fascinating resources of

How does the scientific police work?

How does the scientific police work?(Le Mag de France Bleu Poitou) Television loves forensics, because there are crimes, investigations, motives, and we get to see

Forensic science, clue hunters

Tarbes: Scientific police, the clue hunters La nouvelle république des Pyrénées : November 4, 2021 The technical and scientific police of Tarbes opened us the

Lemerle case: traces of blood revealed by Bluestar

On the first day of Vanessa Lemerle’s trial for the violent confinement of her brother Le quotidien : October 26, 2021 On the first day

A state-of-the-art portable crime lab

Costa Rica’s First Female Forensic Biologist Designed a State-of-the-Art Portable Crime Lab MENAFN : 18.09.2021 In 2010 Tatiana López had to present a University project, she was

“With the blood in the eye” Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials.

“With blood in the eye”. Romano et al. Axis 1 – Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials. Presentation of the paper “With blood in the eye”. Revealing and

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches