A commission of the local police force transferred Juan Carlos Monsalve from Viedma, accused of being the perpetrator of the femicide.

Agustín Martínez

LMCipolletti : 30.05.2021

This Sunday the second person arrested for the femicide of Agostina Gisfman was transferred from the town of Viedma to the capital of Neuquén. This is Juan Carlos Monsalve, accused of being the perpetrator of the femicide of the 22 year old girl from Cipole, who was murdered and then burnt in a rubbish dump in Centenario.

Agostina went to a meeting, which Gustavo Chianesse had arranged for her, at the roundabout at Rutas 151 and 22 in Cipolletti on Friday 14 May at 7pm.

To do so, she asked an acquaintance to take her to the agreed place and once there, she got into a dark vehicle. That was the last time Agostina Gisfman was seen alive.

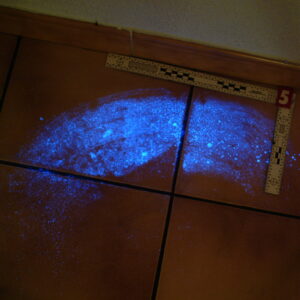

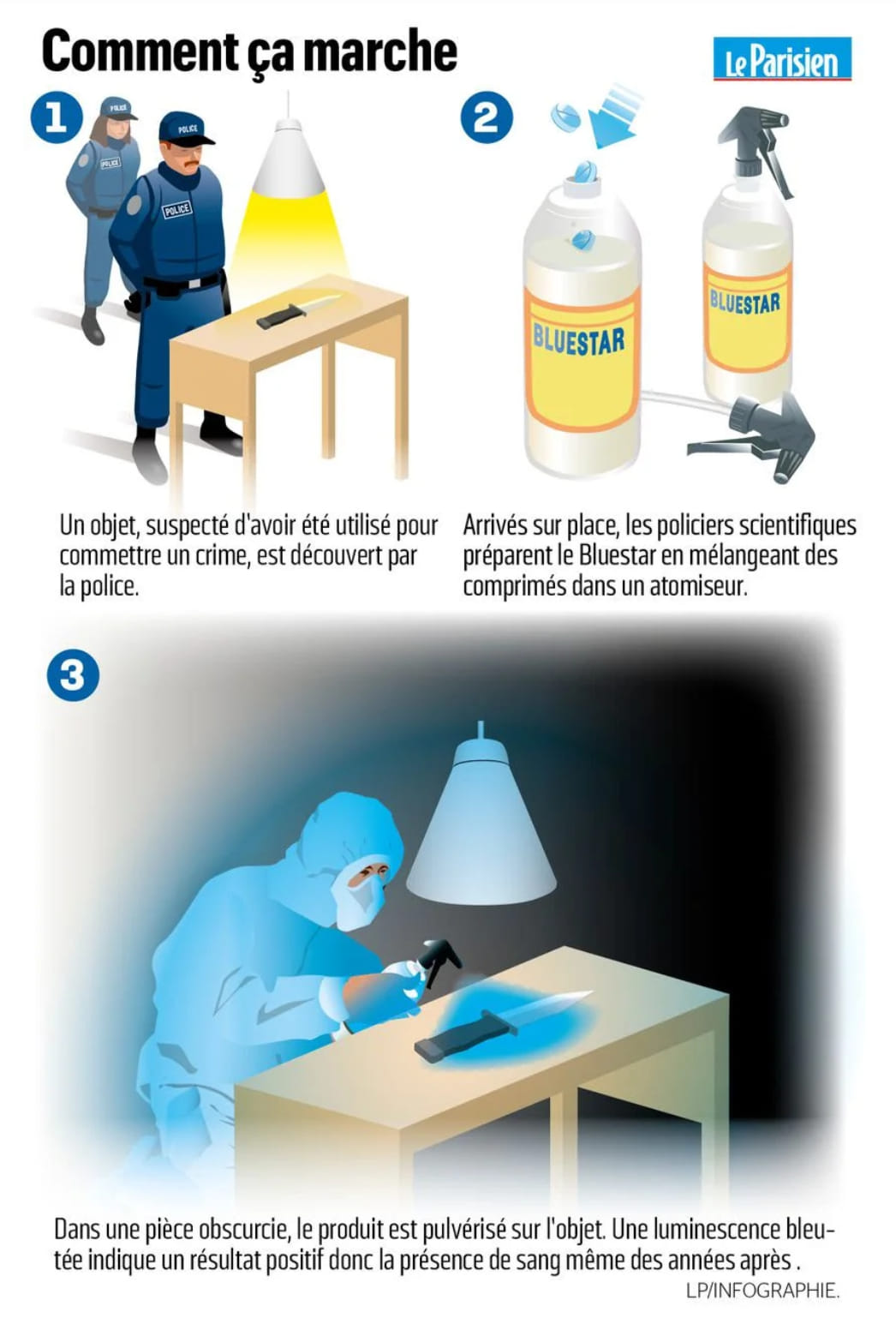

Investigators believe that the young woman was killed with a stabbing weapon on board the vehicle, which evidence suggests was the Chevrolet Tracker van seized last week where human blood was found after a bluestar test.

The femicides then went to a rubbish dump in the town of Centenario, where they dumped the young woman’s body and burned it. It was found there the following day by a person passing through the area.

To date, two people have been arrested for Agostina’s femicide: Gustavo Chianese, already accused as a necessary participant, for being the one who handed over the girl when they agreed to meet; and Juan Carglos Monsalve, suspected of being the perpetrator, taking into account how the telephone antennas located him at the meeting place and the place where he was found.

These were reached as a result of key wiretaps that link them both to the planning of the young woman’s femicide, after Monsalve had a conflict with his wife as a result of the encounter he had had with Agostina in April. When he was unable to locate her in order to “kill her”, as the prosecutor’s office stated in its theory of the case, he asked Chianese to look for her.

It is even known that Monsalve had rented the Tracker on the same day of the femicide, hours before, that is, on Friday 14 May. The same dark vehicle was captured together with another lighter-coloured one by a camera in a house, near the area where the young woman’s body was dumped.

Monsalve had been arrested on 18 May in the town of San Javier, in Río Negro. Finally, this Sunday, his extradition was finalised and therefore, a commission of the Neuquén police travelled to the capital of the neighbouring province to bring Agostina’s alleged femicide to Neuquén. Now, the prosecutor’s office is expected to request a hearing for the formulation of charges in the framework of the case.