Forensics, how does it work?

Crime scene, DNA, ballistics, the role and excesses of files

Le Monde : 10.01.2010

Forensic investigators are the new heroes of American series – Les Experts – and French series – RIS Police scientifique.

Since 2003, forensic scientists have been using a new molecule that reacts to iron ions in the blood, Bluestar luminol, which is active in the dark

Every week a DNA analysis makes the headlines, as we saw this autumn with the traces found on the envelope of the Grégory case’s corbel, then during the escape of Jean-Pierre Treiber… But how does the real French scientific policy work? To find out, I went into the laboratories of Marseille and Lyon, interviewed investigators, met researchers who are passionate about police investigation work and are bound by their professional code of ethics – and noted the growing, and worrying, importance of DNA files in solving criminal investigations

REPORTAGE (published in part in Le Monde Magazine, January 2010)

1- WHERE WE ATTEND THE MORNING TOUR OF THE FORENSIC LABORATORY OF MARSEILLE

We have hair traces in 4522, the case of the robbery with kidnapping of elderly people. Hair was found on the adhesives that bound them.

Coffee in hand, the head of the “Biology” section opens the discussion in a small, low room. The eight heads of department of the Marseille forensic laboratory, engineers and former doctoral students, dressed very casually, meet for the morning’s overview – the “demand review”. Philippe Shaad, the director, the only one wearing a tie, looks stern and says: “We have to try to prioritise. “

That morning, 16 files and 58 coded and numbered seals arrived for biology alone, transmitted by police services in a hurry. Most of them are from robberies and burglaries. There are several DNA samples from ‘individuals’ (the police always say ‘individual’), bloodstains and a swab from a telephone cable.

-The other emergency is 4777, the homicide with a presumption of rape,” continued the Biology Officer. We have 21 stab wounds, blood. The body has been moved, we should see if we can find any plants. He was outside for a long time, and as it has rained a lot, I’m afraid that the DNA won’t tell us anything. We should do some more tests, and concentrate on the car, seal it up… maybe we’ll find some usable traces.

-Well, I’ll call the Commissioner,” says the director. He’s feeling the pressure. Speeding up the result is his job – “I have to streamline” he says.

INPS Marseille handles 500 cases per month, thousands of seals

Since the Sarkozy law of 2003 on “Internal Security” and the methodical collection of DNA by the police, requests to the forensic police have soared. “We are moving from the craft to the industry,” explains Philippe Shaad.

The floor is given to the “Fire-explosions”. Big suspense. Because that morning, a heavy gun battle once again made the headlines in Marseille. Machine-gunned in front of the Velodrome stadium” headlines La Provence. What happened?

At around midday, two individuals wearing black helmets fired automatic pistols and Kalashnikovs at a man who was leaving a gym. Ten bullets, head and chest. The man, a former released bank robber, was suspected of having shot a known gangster in September 2007. Revenge, no doubt. Before fleeing, the two assailants set fire to their car. The men of the “fire and explosion” unit are trying to identify the explosive used. If it was a grenade, they will be able to cross-check. If it was a Molotov cocktail, they will analyse the fuses and the petrol.

Why did the killers set the car on fire? To remove traces of DNA. It’s become commonplace,” a sergeant explained. Banditry, large and small, as Vidocq well recounted in his memoirs (1828), has always adapted to advances in police expertise. Today, to eliminate DNA, they “blow up the stuff” as Chéri Bibi used to say.

Now it is the turn of “ballistics” to intervene. The technicians analyse the cartridge cases discovered after the Vélodrome shooting. Each weapon has a “fingerprint”. In Marseille, the police are used to the use of Kalashnikovs by the milieu. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, it has become the favourite weapon of the small-time crooks of the French Riviera.

New case of the day, toxicology expert causes a stir:

We have a drug rape, with blood on cotton wool. The sample is insufficient. It is not suitable for our analysis.

Director’s ticking. Slowdown in sight. What’s the difference between “narcotics” and “tox” experts? The former deal with seizures of hard drugs that have not been consumed – the port of Marseille was the port of the “French connection” – but also with hashish from Morocco, sold by the small-time kings of the cities – at war with each other. They try to identify the drugs, the cut products, and then compare them with the substances seized in several cases to trace the networks.

The “tox” people confuse drunk drivers, stoned people responsible for an accident, or process substances found in dead people: carbon monoxide, drugs, chemicals, etc. They do forensic work. They do forensic work. What else did the ‘tox’ do on 25 September 2009? Three roadside alcohol tests. The usual.

2- WHERE WE LEARN THAT FORENSIC SCIENTISTS ARE NOT POLICEMEN AND DISCOVER THE HISTORY OF "CRIMINALISTICS

In France, police experts are not multi-skilled super-cops capable of detecting a micro-trace of blood, conducting a profiling interview of a serial killer and then drawing their weapon faster than Agent Catherine Willows in “CSI Las Vegas”. In fact, the jobs of police investigation, evidence collection and forensics remain separate – unlike in the series “RIS. Police Scientifique”.

When a crime occurs and the investigation begins, the forensic identification officers, the “ijists”, “freeze” the “crime scene” on the spot. Trained for this, gloved, masked, protected, they put up barriers, make sure that no one, journalist or neighbour, comes to pollute the place by spitting or with their shoes. Then they take photographs, make sketches, record clues and DNA samples, which are then placed under seal by the judicial police officer. The investigators then call in the services of the forensic laboratories.

In France, three-quarters of the ‘experts’ are not police officers, but former doctoral students from science faculties, engineers and technicians working for the magistrates and the judicial police. These researchers are also civil servants of a public establishment, the Institut National de la Police Scientifique (INPS), which groups together all the technical and scientific police services: biology, ballistics, trace documents, fingerprints, fire-explosions, physical chemistry, narcotics, toxicology, technological traces, all the ‘forensics’.

French forensic science has a long history. Some historians trace it back to the investigation of the “poisoners of Versailles”, conducted by La Reynie under Louis XIV. But the pioneer was Edmond Locard, Alphonse Bertillon’s colleague, who founded the first technical police laboratory in Lyon in 1910…

We are in the Third Republic, Jules Ferry is educating the countryside, and a republican and positivist impulse wants to make us forget the brutal practices and the political filing of the Second Empire police. Edmond Locard wanted to replace the traditional police search for witnesses – unreliable – with the methodical search for convincing evidence – the constitution of proof – and the obtaining of confessions – “the queen of proofs” often obtained by sequestration and beating (formerly by the dreadful questioning or torture) – and sometimes retracted.

With anthropometry, dactyloscopy (fingerprint analysis) and the search for clues, Edmond Locard set the roadmap for a more objective police force: “No individual can stay in a place without leaving the mark of his passage,” he wrote, “especially when he has had to act with the intensity that criminal action requires…”.

Modern French forensic science was really developed at the initiative of the socialist Pierre Joxe, following a distressing report on the state of the premises and equipment of the technical police

In 1985, he allocated significant funds to them, hired scientists and engineers, and brought together all the laboratories and archive and documentation services. This reunification continued under the Jospin government with the authorisation of DNA sampling and the creation of the National Automated DNA Database (Fnaeg, initially intended for sexual offences and later for organised crime and terrorist cases) and the law of 15 November 2001 on “Daily Security” (LSQ), adopted two months after 11 September.

This law will be said to be liberticidal by human rights associations for having liberated telephone tapping and punished by prison the refusal to take a DNA sample. It founded the Institut National de la Police Scientifique or INPS, a public institution under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior.

In the opinion of the director of the Marseille laboratory, the separation of police and scientific analysis tasks through the INPS is very important: it preserves the independence of the expertise from police or judicial pressure. The separation of the professions is appropriate because it enriches the investigation. Generally, we hardly know the case we are dealing with. We are objective and neutral. These different views on the same investigation avoid false leads and enrich the investigation. Sometimes, they nuance or counteract the overly fixed “intimate conviction” of a judge or a police officer in a hurry.

In 2004-2005, the appalling miscarriage of justice in Outreau left its mark on the judicial and police apparatus.

What does the director of the Marseille forensic laboratories think?

We never make a judgment of guilt. We answer a question asked by the investigator or magistrate. What make of car is this paint chip found in the wound of an accident victim? Was this shell casing fired from this weapon? Did this person die by drowning? We can go back to an investigator to discuss how he or she collected evidence, or ask to expand the search. The fact that we are not on either side of the fence, neither police nor judge, guarantees our independence. This is well noted on the journalists’ handbook.

3 - WHERE WE DISCOVER THE EXISTENCE OF "FALSE POSITIVES" AND THE RISKS OF "ALL DNA".

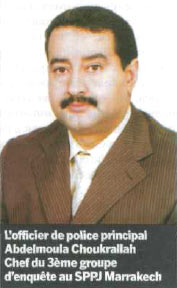

Since 2003, forensic scientists have been using a new molecule that reacts to iron ions in blood, Bluestar luminol, which is active in the dark. Whether the soil has been washed away or the blood diluted a thousand times, there are always a few metal ions left at a “crime scene” – and luminol reveals this by chemiluminescence. Blood traces provide DNA, their projections give ‘morphoanalysts’ clues as to how a blow was struck, how the blood flowed or gushed out.

Many criminal cases have been solved with luminol, such as the sudden disappearance of the Flactif family and their three children in April 2003. But while luminol is an effective detection product, beware of misinterpretation. It also reacts to copper, blood in urine, faeces and sodium in bleach: it could, for example, indicate a walker who has relieved himself in the wrong place. This has happened. All the experts in Marseilles say it: technology is useful for an investigation, it does not give the truth.

Forensic science, how does it work? (Audio)

IAI Annual Educational Conference 2023

August 20-26 Maryland BLUESTAR® Forensic will be present at IAI 2023

Forensic PSA Test: BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA® – The Essential Tool for Crime Scene

Forensic PSA Test: “BLUESTAR® Identi-PSA®” An Essential Tool in Forensic

Rose Petal Murder: The Case Involves the Use of BLUESTAR® Forensic Reagent

The brutal murder case of Christina Parcell in South Carolina

BLUESTAR® at the 75th AAFS Conference

American Academy of Forensic Sciences 75th Anniversary Conference The American

Chemical indicates the presence of human blood in the trailer

After detectives photographed the inside and took some items into

KU Leuven Students Investigate Virtual Crime Scenes

Investigating murders as a forensic expert… (India Education : Apr

Forensics, the latest methods

When pollen and insect larvae are used to solve criminal

How does the scientific police work?

How does the scientific police work?(Le Mag de France Bleu

Forensic science, clue hunters

Tarbes: Scientific police, the clue hunters La nouvelle république des

Lemerle case: traces of blood revealed by Bluestar

On the first day of Vanessa Lemerle’s trial for the

A state-of-the-art portable crime lab

Costa Rica’s First Female Forensic Biologist Designed a State-of-the-Art Portable

“With the blood in the eye” Bioarchaeology and Biomaterials.

“With blood in the eye”. Romano et al. Axis 1

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on 2021 Searches

Canine Handlers and Forensic Specialist Testify in Smart Hearing on

IAI Annual Educational Conference

Find us at the IAI Annual Educational Conference Nashville August 1-7

Troadec case: traces of blood, burning of the bodies, the word of the experts.

The trial of Hubert Caouissin and Lydie Troadec continued with

Alleged serial killer: new excavations and Bluestar in the orchard

Could the crime scene at Mare-d’Albert be hiding other sordid

Police brought Agostina’s alleged femicide to Neuquén

A commission of the local police force transferred Juan Carlos

Detecting Blood in an Outdoor Environment with the Bluestar Reagent and DNA Analysis

Author(s): McCall, Keenan; Woods, Grace; Richards, Elizabeth Type: Article Published:

Thomas Lesire trial: These clothes are examined with Bluestar reagent

Assizes: trial of Thomas Lesire, accused of the murder of

Daval case: investigation and use of Bluestar

Daval trial: life sentence requested against Jonathann Daval accused of

Case of a missing youth: raids and investigation procedures continue

The procedure was carried out jointly with police personnel from

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after 2 years

Galveston AA group leader’s killer is still out there after

He had tried to erase the trace of the victim’s blood

The baby was beaten and tortured, recorded in bruises, scratches,

Policeman’s Memory : a barbaric crime!

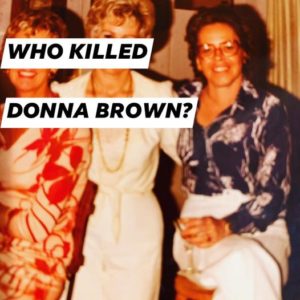

By Fadel ATAALLAH – POLICE magazine N° 57 Octobre 2009

Narumi case: investigators accuse the main suspect

The Chilean ex-boyfriend of this Japanese student who disappeared in

Christine Wood’s DNA found in Brett Overby’s basement, court says

CBC NEWS : 02.05.2019 Christine Wood’s blood was found on

Bluestar, the miracle product that solves many criminal investigations

Bluestar, which was developed in a CNRS laboratory, has become

Justice for the Lyon Sisters

How a determined squad of detectives finally solved a notorious

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Jealous husband in South Africa kills his wife’s lover.

Murder of a woman by her son

This matricide was solved by the French Gendarmerie Nationale using

Alexia Daval case: other acts and hearings to come

L’est Républicain : 07.07.2018 New forensic expertsAbout forty experts of

JESSIE BARDWELL CASE: WAS TEXAS WOMAN’S DEATH AN ACCIDENT OR MURDER?

A father dreams his daughter has been killed, then she

They capture the partner of a mannequin

The subject claimed that when he arrived at the apartment

Scientific advances have made a blood trail speak for itself

Maëlys: how scientific progress made a microscopic trace of blood

Invisible bloodstains revealed by Bluestar

Mallouk case: the long trial of a murder without a

A matter of gold and blood

BEHIND THE DISAPPEARANCES OF ORVAULT, THE TROADECS’ FAMILY TRAGEDY (France

Killer of elderly woman confesses he had help from hitman

Puno: the killer of an old woman confessed to having

The murderer of an old woman confessed to having been helped by a hitman

Puno: the murderer of an old lady confessed having been

The scene of a crime, suicide or natural death has no mystery for the “cleaners”

It’s a job that is rarely mentioned, as if to

Improved detection of Luminol blood in forensics

Review: Improving Luminol Blood Detection in Forensics Florida Forensic Science

Officers get forensics training

A couple dozen first responders and crime scene investigators gathered

Photographing bloodstains

Photographing bloodstains: Bluestar reagent FORENSICS 4 AFRICA 07.07.2016 (Nick Olivier)

Mystery around a disappearance

Yves Bourgade’s murder: BLUESTAR® FORENSIC strengthens suspicions about his wife…

Nisman case: the conclusions of the criminal report

Nisman case: conclusions of the official criminal report point to

Traces of blood were found in his marital home, revealed by the “Bluestar”.

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

The judge in the Yexeira case accepts as evidence another piece with blood on it.

To complete the process of authenticating the evidence, the magistrate

20 years of forensic bloodstain analysis in Ontario

While University of Windsor students play with spatter at a

Chief Warrant Officer Benitez left a bloody trail

The clues are accumulating around Chief Warrant Officer Benitez and

The Flactif case: An investigation solved with Bluestar

At a crime scene, he makes the bloodstains talk “When

Photographer Exposes Crime Scenes, With a Dash of Chemistry

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

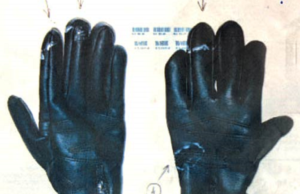

Bloody gloves in Israël

Bloody gloves “catch” Israeli attorney Anat Plinner’s murderer…

Forensics, how does it work?

Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share

Flactif, The cursed cottage is for sale

The parents of Xavier Flactif, massacred with his family in

The blood of two confederate soldiers revealed at Gettysburg

Gettysburg Civil War case revealed after 142 years !

Suspect arrested on crime scene after his arms turn blue !

A man arrested after his arms turn blue…

The secrets of real experts (LE FIGARO)

Philippe Esperança, morpho-analyst: Blood on the trail By Le Figaro,

The Flactif case: With Philippe Esperança

BLUESTAR® FORENSIC helped solve the Grand-Bornand quintuple murder case The

Shooting of a pedestrian by a driver

A driver shoots and kills a pedestrian…